The 2009 Munich Film Festival

By Leslie Weisman, DC Film Society Member

Photo from the Munich Film Festival website.

Film festivals are renowned for honoring icons of the past and present with awards and encomiums, and for drawing stars to their stages with premieres of their latest films. Rare, however, is the fest that manages to do it all — and still convincingly bill itself as a low-key, public-oriented, “come one, come all” event.

The Munich Film Festival (Filmfest München), which in June celebrated its 27th year, is one that does. And while it may not be Europe’s largest film festival, it is increasingly becoming the fest to go to if you love film and all it’s capable of, and want the inside track in an intimate setting surrounded by fellow film lovers and the top tier of classic and cutting-edge filmmakers. Festival director Andreas Ströhl, who told Variety shortly before the fest’s opening this year that between 60,000 and 65,000 attendees were expected, was able to report at its end a record-breaking 73,500 tickets sold — 8,000 more than 2007’s heretofore record total, and a 15 percent increase over last year. Variety has even (as only Variety can) coined a classy catchphrase, calling it “a discerning festival with movie lovers in mind.”

Whisky with Vodka

That it is, and one with a reputation for shaking an intoxicating cocktail that’s equal parts screening showcase, movie set and cinema lounge. So it seems apropos to open this report with one of the fest’s most delightful surprises, Whisky mit Vodka (Whisky with Vodka, Andreas Dresen, Germany, 2009) an early favorite to win the Audience Award (it would ultimately go to the irresistible Keep Surfing), which would a few weeks later win for Best Director at Karlovy Vary [International Film Festival].

The press screening was at Munich’s — indeed the world’s — oldest continuously operating cinema, the elegant Neues Gabriel. Like the Neues Gabriel, Whisky with Vodka harks back to an earlier time — when an alcoholic East German film star who was deemed a production risk was doubled with a second actor who could fill in when the first fell off the wagon. The “competitive situation” had the intended effect: after two weeks, the star pulled himself together and was able to finish the film.

In an interview, screenwriter Wolfgang Kohlhaase was asked if there was anything in the story that was especially close to his heart. “It was important for me to tell about [the star’s] father who was a mailman,” he said. “I wanted to show that outside the cinema, there’s still the real world — and that sooner or later, inevitably, it will appear. There’s one question that runs like a leitmotif through the film,” he continued. “How much of real life is in cinema? And how much cinema is there in real life?”

Of all the films seen at a film festival, the American indies should, almost by definition, have a monopoly on “real life.” Real life being what it is, though, at this year’s Filmfest München, the indies were both true to form and utterly unpredictable. Their theme? Out of it (“Neben der Spur”).

Everything Strange and New

Not true to life, but out of it? Wait: “... the tension between I and WE, between the individual and society.” Of course: The characters are “out of it,” not the films. But there’s another subtlety: Not the usual I and they, but I and we. These are characters who are out of it even among outsiders. In Everything Strange and New (Frazer Bradshaw, USA, 2009), which would win the CineVision Award for a film that is “innovative, goes in new aesthetic directions and is an outstanding contribution to the cinematic arts” (just weeks before, it had won the FIPRESCI prize in San Francisco) we see the woes of the middle class in times of financial crisis: You work like a dog, put aside every penny to buy or build the house of your dreams, and then? “You live where you can’t afford to do anything but hang around your f—ing house.” And hanging around the house soon loses its charm. Such is the lot of carpenter Wayne, who loves his wife and kids — “The kids are the best thing that ever happened,” he tells a friend — but has begun to ask himself the dreaded questions: Whatever happened to the hopes, dreams and promises of my youth? Is that all there is?

“We were persuaded by its fascinating structure and its style, its way of telling the story by means of a curious camera that never stops or lingers, observing the actors as they move through a rich and complex set,” wrote the jury. “Cups, flowers, sofas, streets, roofs, houses — all are storytellers. It is the human story of mediocrity, of doubt, challenge and the consuming wish for change that unfolds in this film, told in a way that keeps the audience on tenterhooks till the end. An approach toward minimalist storytelling, a poetic reflection on the conditions of human existence.”

And one told without the slightest hint of pretentiousness, and with a photographer’s eye for the painful absurdities of life. (Bradshaw’s website still identifies him as a DP; the film tellingly credits him not as director, but as photographer.) In one memorable scene we see Wayne, who entertains his small daughters by suiting up as a clown for their parties, respond to his wife’s heartfelt bedtime thanks for being so patient with her (her moods can turn violent), with a silent grimace, in full clown regalia. Swish pan, back in his PJs, he croaks an expressionless: “Glad I could be of help.” Guy talk between the beleaguered and confused Wayne and a dealer friend as they watch a porn film veers off into unexplored (for Wayne, anyway) territory which, in the hands of any other filmmaker, could be a turn-off for viewers of delicate sensibility when he says it’s been a while since he’s had a blow job, and his friend offers to oblige. Here the scene is played to perfection, a telling mix of pathos and hilarity.

Accepting the award, Bradshaw said that he was “really honored” to win it, “especially at such a distinguished festival as Munich,” adding: “It’s really gratifying to know that people get it.” Indeed; from the press notes: “My personal project as a filmmaker is to create work that opens viewers to themselves... For me, life is a tiring but amazingly gratifying struggle to find meaning.”

Journey of an Olive Tree

The attempt to make sense out of life is a theme frequently embraced by indie filmmakers, but not unique to them. In the absorbing documentary film Journey of an Olive Tree (Anton Pichler, Germany/Israel, 2009) the search is both literal and figurative, the struggle not just of mind and heart, but of will and physical being. In a larger sense, it is also a microcosm of the internecine and international conflicts that have ravaged people and countries throughout the world, regardless of race or creed. A project of the peace-seeking organization “Breaking the Ice”, the film follows the journey of 10 travelers from 10 different lands, each of whom has suffered personally and profoundly from an intractable military conflict — sometimes at the hands of one of the others’ countrymen — on a mission that seems doomed from the start: to plant an olive tree (they name it Oliver) in Tripoli, Libya. Why? As an international symbol of peace, the olive branch, thus the tree, will be a tactile, enduring symbol of the ability of people to live in harmony despite the differences that divide them. If they can make it on this grueling journey, or so goes the hopeful reasoning, so perhaps can their countries and, looking to the future, their peoples.

There is the New York firefighter who reflects on having lost 343 friends and colleagues on 9/11. “The dust is still in my shoes,” he tells us; there is no doubt what he means. He is wearing them on the journey: “I feel like I brought them with me.” He pauses, gathering his thoughts as tears form in his eyes and he tries to force a smile. “Hopefully, it’s the beginning of peace... so they didn’t die in vain.”

There is the former “body double” of Udai Hussein who was tortured by both his own countrymen and the CIA, and the former Israeli fighter pilot, tortured by guards in a Damascus prison. There is the Palestinian student whose best friend was killed by Israeli bullets, and the Israeli teacher whose mother was killed by a suicide bomber as she traveled home on a Tel-Aviv bus. There is the Iranian film director who made a documentary about the Iran/Iraq war after losing her best friend to it, and who now works to promote dialogue between the two nations.

There is the Ukrainian soldier who volunteered during Operation Iraqi Freedom and is still haunted by horrific visions of combat, the comrades he lost and the young men he killed. There is the seething Afghan refugee who cannot forgive America for the destruction wrought in his country, and the Vietnam veteran who, with memories of his own wartime experience and disillusionment, seeks to deflect the Afghan’s anger. And there is the Tibetan monk, witness to the recent violent uprisings in his country, who serves as a silent observer to the heated exchanges.

All hardened victims of lethal conflict, none under any illusions about this quixotic, maybe even simplistic quest, but all, abjuring experience and maybe even common sense, willing to try. There will be strong disagreements, at least one becoming physical; there will be apologies, one heartfelt, one forced; there will be surprising reconciliation, and a surprised realization — from those representing the two seemingly most irreconcilable sides — that “we are the same.”

“You cannot solve a problem with the same kind of reasoning that created it,” concludes one of the participants in a voice-over; is it the Afghan? If so, it is entirely apt. For it is not only his nation and its people who must wrestle with this conundrum, but also those who have used them as proxies for their own power games.

Fixer: The Taking of Ajmal Naqshbandi

In Fixer: The Taking of Ajmal Naqshbandi (USA, 2009), for which director Ian Olds was named Best New Documentary Filmmaker at Tribeca (the film premiered on HBO in August), corruption has become so endemic in a country that once choked under the yoke of the Taliban that many who yearned for democracy now despair at what it has wrought or enabled, or at the very least, failed to contain.

Ajmal Naqshbandi is a fixer — and here I quote from writer Robyn Hillman-Harrigan’s intro to her Huffington Post interview with Olds, because her definition is complete: “... a local person who makes contact with potential sources, estimates the level of risk in traveling to various areas and then facilitates the actual journey by driving the foreign journalist to the rendezvous points and serving as translator while there.” Ajmal (who is referred to by his first name in the film) is hired by Christian Parenti, a reporter for The Nation whose book, “The Freedom: Shadows and Hallucinations in Occupied Iraq,” inspired Olds to develop what started out as a fiction script about a journalist and his translator. A series of occurrences over the next couple of years would lead Parenti to contact Olds and invite him to accompany him on his next trip to Afghanistan to research his film. It is that journey, facilitated by Ajmal and shot both by Parenti in the Jeep and by Olds following behind — and the fate some months later of the young fixer — that the film portrays. “Nothing’s happening here,” we hear Ajmal assuring Parenti early on. “It’s safe here. Of course there are bandits and thieves, but...”

It is not the bandits and thieves that Ajmal will have to worry about. Kidnapped along with the Italian journalist he is then accompanying by members of the Taliban, reporter and fixer are immediately accused of being spies, their insistent cries that “We’re journalists!” unheeded by their captors. Olds’s film would now have an unwanted postscript: It is in part in Ajmal’s memory that the research footage that was never to be screened for an audience would instead become the heart of a documentary seen (assuming a large HBO audience) by millions.

At the “cinetalk,” a rare, hour-long presentation held independent of (and prior to) the film screening, Ian Olds spoke with Katherine Crocker, American consul in Munich, and Ute Wagner Oswald, a Munich journalist and documentary filmmaker, about the experience of making the film. The film shows how there was a botch-up in the release of Ajmal, who was to be exchanged along with the Italian journalist for five Taliban prisoners, Olds explained. The Taliban then demanded a separate exchange for Ajmal; when it didn’t happen, he was beheaded. When Olds learned of it, he told us, he was so distraught he didn’t want to continue. But he had so much material, he felt that he owed it to Ajmal to tell his story.

Olds had been to Iraq, having gone there out of a sense of “anger and disbelief” at the U.S. invasion, seeing no connection between it and 9/11. From the get-go he was “much more nervous” about going to Afghanistan; having returned unscathed from Iraq, “I thought my luck might be running out.” In her repeated travels there, said Wagner-Oswald, she avoided known Taliban areas entirely, feeling that the potential gain “wasn’t worth the risk.” The job of the fixer is inherently perilous, she continued, but the pay is exponentially higher than what one could earn elsewhere in the region, so those who are brave, skilled or desperate, or all three, take a chance. Ajmal, who was all three, was supporting a large extended family, so the risk probably seemed worth it. Editors demand exclusives and exciting stories, she added, so there is additional pressure to deliver; if you don’t, your job — and the money it provides — will go to someone else.

The dangers on the ground are more subtle, but more lethal. “You just have to realize you’re in a different world. Journalism is not part of their culture,” said Wagner-Oswald. Despite the perils that threaten foreign journalists, added Olds, it is the Afghan fixers who face the bigger risk. “The Western journalists go home to their families, friends and countries”; the fixers must remain behind. “It is important to refer to the fixers as journalists, which they are, because the word ‘translators’ could put them in danger,” suggesting complicity with foreign powers, he noted. On the other side of the ledger, not speaking the language also opens the possibility that your fixer may not always translate things correctly, either out of fear or because he sees advantage in making a situation seem otherwise. Trust is essential, said Olds, but to be on the safe side, it’s always best to have more than one person with you who speaks the language.

There are many theories as to who actually engineered the kidnapping; the Taliban, we were told, sold the film of Ajmal’s beheading to the Italian government for $15,000. It is now being circulated widely, and even sold online. Olds quietly and movingly acknowledged the difficulty of reconciling the personal tragedy of Ajmal’s death with the fact that it is his murder that makes the film a draw.

The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus

It was not murder but a sudden death that made the opening-night film even more of a draw than it would be under normal circumstances. The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus, a French-Canadian-United Kingdom co-production by the maverick, multiple award-winning expatriate American director Terry Gilliam, features the late Heath Ledger in his last film. A movie that should be viewed at least twice but with sufficient time to let it settle, seeing it at the premiere was like being served a gourmet banquet of cinematic sounds and visuals, historic references and CGI capabilities without having time to breathe between courses. “We wanted as many people as possible to see the film,” Gilliam deadpanned as he introduced it to the audiences that filled several halls in the magnificent, $250 million Mathäser multiplex. “So we made it so it would look great on iPods. So I apologize if it doesn’t look good on these huge screens.”

On the contrary, the film, a feast for the eyes and the imagination, viewed in miniature would challenge not only one’s eyes, but one’s sanity. A traveling theatre-cum-carnival that gives shows in run-down London neighborhoods from the back of a 19th-century caravan has a repertoire of illusions and tricks that would be impressive — if only they worked. More often than not, however, they don’t, and the aging wizard Dr. Parnassus is compelled to take on a man the troupe saves from being hanged by pirates, who has an uncanny — and, it will turn out, unscrupulous — knack for making things work.

Aided by the doctor’s comely daughter Valentina, her lovesick admirer Anton and Parnassus’s indispensable factotum, a wisecracking (and wise) midget named Percy, Tony makes the troupe’s show successful beyond their wildest dreams, before it all (literally) comes crashing down around them. It’s all done with mirrors, and what’s on the other side rushes by so quickly in sometimes related, but more often disjointed yet arrestingly imaginative vignettes employing eye-popping computer graphics imagery, it’s hard to get a handle on exactly what’s happening at any given time. It’s not all smoke and mirrors, though. For Dr. Parnassus, now facing the end of his unnaturally extended life, made a deal with the Devil, who promised him eternity, but with one hideous condition. And Mr. Scratch, in his chillingly sly but businesslike manner, has come to collect.

The podium discussion was scheduled for 10:45 p.m. but began more than an hour later to allow Gilliam time, we were told, to disengage himself from his many admirers after the screening. The crowd at the Gasteig, meanwhile, had started gathering an hour before the scheduled start time; it would be the largest gathering for one of these discussions this reporter had ever seen. Gilliam told us that the complex story began in his mind, quite simply, with a wagon. Asked about the source of financing, Gilliam said that it was multinational and expressed astonishment that despite the presence of Heath Ledger (who played Tony) in what would be his last screen appearance, only Hollywood refused to contribute. (He was, he told us, in negotiations for U.S. distribution; a news release in mid-August announced that Sony Pictures Classics had picked up the film.) Asked about his legendary, long-delayed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, Gilliam said he is again working on it and hopes to have it finished by next spring.

But back to Imaginarium: The cast and crew froze in London, where it was bitter cold during the filming, but were more committed than ever to finish the film after Ledger died. When the producers declined to pay his family for the work he had completed, Gilliam said, the other actors banded together, agreed to forego their salaries, and signed them over to Ledger’s family in tribute to him.

The idea of the mirrors was fortuitous in that it allowed Gilliam and his co-writer Charles McKeown to cast other actors ((Johnny Depp, Jude Law and Colin Farrell) in the role of Tony to reflect other aspects of his character. It wasn’t easy emotionally, continuing on after Ledger’s death. Somehow, though, it seemed almost as though he were watching them. “Heath was old and wise beyond his years,” said Gilliam. “He affected all of us,” added Verne Troyer (Percy). “It was as if Heath left us a legacy of clues, directing us where to go with the film.”

Does the film hold any personal meaning for Gilliam? “It’s a bit transparent, this one,” he said, in that the character of Dr. Parnassus is contemplating the end of his career. Gilliam praised his cast to the skies, singling out Tom Waits (the Devil) and Andrew Garfield (Anton); Troyer commented that watching Christopher Plummer (Dr. Parnassus) “was like a master class.” Ledger created much of his character as he went along, fleshing it out, said Gilliam, and did a lot of ad-libbing. It wasn’t long before Garfield, playing opposite him, joined in. Why didn’t you use the music of Tom Waits, who in addition to being an actor is also an ASCAP Award-winning (for the TV crime drama “The Wire” in 2004) and Oscar-nominated (for One From the Heart in 1983) composer? “Tom just wanted to be an actor here,” said Gilliam.

The Tour

In Turneja (The Tour, Serbia, 2008), a very ready-for-prime-time film from the celebrated Serbian director-writer Goran Markovic, a bankrupt Belgrade theatre troupe goes on the road in war-torn 1992 Yugoslavia to entertain the troops. A noble endeavor to be sure, if one that could have used a tad more forethought — the latter being regrettably at a premium, fueled as our delightfully over-the-top thespians are by their duel (and sometimes dueling) backstage passions for gambling and the grape. The film won last year’s FIPRESCI Prize in Montreal, where Markovic also was named Best Director.

As they travel through the countryside, their rickety van by turns bouncing and leaping as a series of electrifying explosions, machine-gun fire and land mines (“That’s normal,” shrugs the driver as the terrified players grab their ears and hit the floor) interrupt their animated arguments about what play they should stage and who should play what part, the personality of each of these characters, at once archetypes and individuals, comes vividly to life. So, too, do those of their audiences and antagonists, as do the dangers all of them face — or create.

“It would be hard to shoot a movie about this war,” muses the weary-eyed doctor as he washes his hands, forgetting he’s already done so, “because the warring parties all look the same. You couldn’t tell the difference.” Indeed, the deep-seated internecine hatreds that would become fodder for international news headlines and for pleading, pontificating or dispassionate commentary — and for action that was, for too many, too little and too late — have so warped the hearts and minds of the combatants, they treat their own with the same icy indifference that allows them to brutalize their nominal enemies. In one unforgettable scene, a Croatian commander — who recognizes the bedraggled troupe and is apologetic that one of his soldiers, no doubt certain that this is what his commander would do in his place, has ordered them to walk across a plain seeded with land mines — calls them back. With a cold deliberation veiled by nonchalance, he tells the terrified young man to prove to them that there’s nothing to worry about, by going first. In a powerful economy of means we see nothing but the weathered face of the older actress in close-up as disbelief, supplication and agony flicker swiftly across it; ending at last, her lips moving rotely, rapidly, in what can only be a silent prayer for the dead. In the distance, the cries of the young soldier can be heard, imploring; the actors can only watch in horror. As did the world.

The Necessities of Life

The world is also watching — if only briefly — in Ce qu’il faut pour vivre (The Necessities of Life, Benoît Pilon, Canada, 2008), Canada’s contender for Best Foreign Film at last year’s Academy Awards. A stunningly photographed and quietly moving “salute to the Inuits of Canada and to the survival of their culture,” as the opening title has it, the film has won a slew of awards, including the Capital Focus Special Jury Award and a Capital Focus Award (Special Commendation) at this year’s Filmfest DC.

We are first introduced to the protagonist, an Eskimo hunter-fisherman named Tivii, through panoramic shots of the vast, barren, icy landscape that is his home and museum-like tableaux of the objects and tools that define his life. This distancing sets just the right tone for a docudrama that will slowly, inexorably draw us in, the landscape becoming almost a character in the story of this man and the alien place to which he will be taken, and in which he will spend the next two years: a mainland hospital.

It is the 1950s. Scene: a reverse Ellis Island-style processing activity aboard a ship, where people are being examined prior to boarding rather than disembarking. Tuberculosis has hit the island, and those who are found to be afflicted are whisked away to the mainland (Québec) with hardly a word of explanation to them or to their distraught families, few if any of whom speak French. We watch as Tivii takes it all in, his anger and confusion turning first to amazement as he is driven past the “wonders” of civilization, then to profound loneliness as he takes up residence in a sterile hospital room far from his family and the natural world. The relationships he develops there — with his roommates; with a pretty and sympathetic young nurse who helps him learn the language and the culture; and with a fellow patient, a boy who speaks his native tongue and has no family of his own — will help Tivii to survive emotionally, severe setbacks notwithstanding, while the medical staff works to ensure his physical survival.

In a Q&A following the screening, director Benoît Pilon told us that while the characters are fictional, Inuits, who constitute a small minority, did not in fact have linguistic or cultural support during their stay in Québec hospitals. Given the size of the Inuit population and the extreme hardship of the arctic weather conditions, which often prevented the ship from reaching the shore to retrieve passengers, this was not necessarily cause for reproach, he noted. The worst instances involved children who, because of language barriers or administrative error, were never reunited with their families.

Most of the cast are nonprofessional, although Nataar Ungalaaq, who plays Tivii, is a well-known Inuit actor, director and sculptor who gained international recognition for his work in Atanarjuat (The Fast Runner, 2001) and received four Best Actor awards at major film festivals for Ce qu’il faut pour vivre. It was crucial, Pilon said, to have a sympathetic lead actor for the role of Tivii so as to engage audiences’ interest in what might otherwise look at first glance to be a clinical historical documentary. Pilon was also pleased with the work of Paul-André Brasseur, who plays the young boy Khaki and had heard the language (his mother is Inuit) but had never spoken it. After working with the boy to see if he could handle the role, “I knew he had what it took.”

A Whole Life Ahead

Marta also seemingly has what it takes — as does the film that hilariously chronicles her woes, and has screened at festivals from Moscow to Tokyo to Istanbul to L.A., winning major awards at two. But is it enough to be an attractive, intelligent, hard-working, ambitious young woman who has played by the rules and made her mother proud by succeeding gloriously in academia, when it’s time to prove herself in the (sur)real world? Especially when it turns out to be that netherworld inhabited by those who interrupt us with shrill, insistent rings at the worst possible time to try to sell us products and services we do not want, have never wanted, will never want, when all-I-want-is-to-be-left-in-peace-to-eat-my-dinner-thank-you-very-much-goodbye? Tutta la vita davanti (A Whole Life Ahead, Paolo Virzì, Italy, 2008) answers that question in a film that could be described as what might have resulted, were such a thing possible, had George Orwell and Lewis Carroll collaborated on a 21st-century screenplay optioned by Federico Fellini and Vincente Minnelli.

Based on a bestseller that began as a blog, A Whole Life Ahead starts with deceptive infectiousness. Going about her daily business through the streets of Rome in supersaturated color, our heroine contemplates the people she sees in buses and sidewalks, shops and offices, buoyantly bopping to the beat of the Beach Boys’ “Wouldn’t It Be Nice.” Observing them with a puzzled look as if they are from another world, she seems content to watch them enjoy it. For Marta, fresh from a sheltered life spent immersed in the philosophy of Heidegger, has developed her own foolproof philosophy for success: “You just have to figure out the song, and move to the beat.” But real life is more Schoenberg than Beach Boys — ironically, closer to Heidegger, who wrote: “Everywhere, we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral.”

Marta learns this the hard way when, unable to find a job in her field (“This is the film every graduate has waited for, a satire that depicts the tragedy of the gifted but underemployed with merciless wit,” wrote a local paper) she takes a job at a call center. “While Marta’s whole life for all intents and purposes lies before her,” it continues in a choice selection of words, “instead it leads to Career Dead End Street, a blunted being-and-nothingness, a hellhole swampland of capitalism.” Whose devil, I might add, is in the details — and in its satanic boss, a Cruella De Vil of the call center, whose victims are not puppies but employees she drives to distraction, illness, even suicide. And the audience to gleeful — if rueful — recognition. Who among us hasn’t applauded less-than-deserving (well, to our eyes) co-workers at the annual awards ceremony, thinking: “It should have been me up there”? Ah, but Boss Lady takes the bitter pill and turns it into cyanide: Not only are the star pupils lavishly praised and rewarded, but the conspicuously less successful ones are forced to stand and cringe as they are ruthlessly strafed with public humiliation and mockery.

But, again as in life, the Boss Lady (Daniela, played by the luscious Sabrina Ferilli; daughter of an Italian Communist Party official, in a recent poll Italian males from 15 to 34 named her the most loved Italian woman) answers to a higher authority. And, as in the movies, they’ve had a torrid affair that will come to a violent and unhappy end — which many of us on the distaff side will cheer, while deploring the gore.

My Neighbor, My Killer

Everyone — except maybe the aggressors — deplored the gore that ensued in 1994, when Rwanda’s Hutus were incited to massacre their Tutsi friends and neighbors and wound up wiping out some 800,000 of them in little more than three months. As impossible as it may seem, the two sides now have largely made their peace, thanks to an extraordinary initiative by the Rwandan government. In My Neighbor, My Killer (Anne Aghion, USA/France 2009), which some DCFS members may have seen at this year’s Silverdocs, we watch the reconciliation process (Gacaca) in action as friends-turned-enemies return home from prison to face their victims or their victims’ families. They in turn are asked to listen to the others’ confessions, to confront and then forgive them and, in the end, to live with them again as neighbors.

As might be expected, the reactions to this radical proposal are as individual as the people involved, and Aghion takes care to allow each to have his or her say. As does, indeed, the government: No matter how horrific the details or how anguished or incensed the speakers become, they are urged, and at times compelled, to say what for seven long years (it was filmed in 2001) has remained repressed and unspoken. But uniqueness becomes universality as betrayal becomes a common theme of both the testimonies and the follow-up interviews. And while venting is plentiful and to an extent therapeutic, closure is elusive.

“They were our neighbors, our friends,” says a woman. “Do you think I could kill you? But that’s what happened... They grabbed my baby from my back, threw her on the ground, and hacked her to death.” One of the accused acknowledges his part in the madness, as if he himself cannot believe it: “We exterminated each other, although we were brothers.” His words eerily recall those of the doctor in the Serbian film Turneja, quoted earlier in this article, speaking of the other major fraternal genocide of that time. To speak the truth is risky. While many seem to do it safely here, oddly, the one who questions the process itself — “Some really think about it, what it means. Some just do it, like a game: ‘OK, now we stand, now we sit down’” — will die an untimely death.

At the end, some will forgive or be forgiven; others will not or cannot. “We all killed,” says a former Hutu soldier. “We were an attack group. Our mission was to kill, not thinking who or what.” There was no “mission,” objects another. There was no war, there were no patrols; the killing was one-sided. “It was a genocide,” says a third matter-of-factly — is it indifference, or is it horror so unbearable it’s gone beyond the point of feeling? “A genocide to terminate the Tutsi.”

Disgrace

“Everyone is guilty,” was the conclusion of a Munich paper reviewing Steve Jacobs’ Disgrace (Australia/South Africa, 2008), based on J. M. Coetzee’s novel of the same name, which won the FIPRESCI Prize for Special Presentations at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival. Here the tension and ensuing violence are more understandable, for the antagonists are not brothers, friends or even neighbors, but native peoples and their colonizers. John Malkovich’s David, a late-middle-aged poetry prof in Cape Town, South Africa, finds himself in a situation similar to that of another professor who falls deeply in love with a student in Isabel Coixet’s Elegy (also based on a famous novel by Philip Roth), which screened at Landmark's E Street Cinema last year. There is a significant difference, however: the feeling here is not mutual, and David is soundly rejected, then essentially given his walking papers by the school when he doesn’t take no for an answer.

There is another profound difference. In Jacobs’s film as in Coetzee’s novel, the affair is not the heart of the story; rather, it is a springboard to the professor’s entry into a world which he has, through self-interest or willful ignorance, been able to keep at a careful distance. Not so his gay daughter who lives alone on a farm, assisted by a black worker she has known for years and a rifle. Neither of these protections will be of much help when the worker leaves for a few days on family business and a gang of toughs see it as the perfect opportunity to score a hit, both sexual and financial. When it turns out that the worker may have known more about the attack than he admits, David and his daughter begin to see both their own lives and those of the blacks who share their lives and their land from a different, more nuanced perspective.

Shirin

We certainly see things from different and nuanced perspectives in Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin (Iran, 2008), which places us in the unusual position of second-level spectators, watching the watchers. Our subjects are an audience of mostly women at an Iranian theatre watching a 12th-century play, “Khosrow and Shirin.” The play has been staged by Kiarostami for the sole purpose of providing a vehicle for the spectators, all of whom are well-known actors (while most are Iranian, a chador-clad Juliette Binoche is a conspicuous and amusing exception) to react to its melodramatic story. The play remains invisible to the cinema audience; but, as in radio plays of yore, the mellifluous voices paint images in the mind. Here, those images are complemented by the absorbing faces of the audience.

While Kiarostami has been taken to task for this boldly experimental work (it’s supposed to be real but it’s staged, the subtitles are a distraction, the use of famous actors pretending to be average cinema-goers is too precious when it is not deceptive), this viewer was struck by the intensity of the visages, seen in extreme close-up and exquisitely lighted, and the lingering attentiveness of the camera that seemed to be in love with each one in turn. Some are Liz Taylor lipsticked and eye-shadowed in a way that seems to belie the severity of their head scarves. Others are obediently drab, the pallor of their skin in painfully sharp contrast to the Arabian Nights-style vividness of the tale, whose poetry can be swoon-inducing (“Oh water embrace me, caress me like a lover, lather me in pure droplets...”). Some are so caught up in the tragedy of the tale, tears brimming in eyes filled with agony slowly coursing down their cheeks, we are sucked into the intensity of their emotions.

Yes, they are actors. But this is a film experience on several levels. Even if it isn’t a documentary, the faces, photographed as if by a master portraitist, draw us irresistibly to the screen. Would the fact they they were “real people” make the intensity of the viewing experience any more real? Filmgoers generally feel no obligation to apologize for crying at fiction films. And is that not what these women are doing? As is the cinema audience, in watching them? A thoughtful experiment by a filmmaker. And a thought-provoking experience for this filmgoer.

Know Your Mushrooms

There were more than a few thought-provoking filmic experiments at this year’s Filmfest München that were a bit closer to home, not all of them American indies (which have long held a special place in the hearts of Filmfest fans and officials), at least by name. One of these, with the double-take title Know Your Mushrooms, by Canadian director Ron Mann, was a particular pick of fest director Andreas Ströhl, who made a personal appearance at the late-night screening. Ströhl, who told a local film magazine that this was one of the films he was most looking forward to, proceeded to give the nearly sold-out cinema the lowdown on how and why he obtained this doc on the much loved, but often misunderstood fungus.

Returning from Cannes with his team in late May, the Filmfest director was surprised to find a DVD in his jacket pocket. Not giving it much thought and swamped with Filmfest München preparations, he put it aside. Sometime later he received an e-mail from the director, asking if he’d had a chance to screen it and promising he wouldn’t regret it if he did. Sure enough, although the slate had already been selected, “I laughed so hard watching the DVD, I knew I had to invite it to Filmfest.”

And laughter is only the half of it. This exploration of Everything Mushroom is an eclectic, psychedelic, kaleidoscopic, kinescopic, multimedia celebration of fungal fact and fiction. From frames of a 19th-century silent depicting long-bearded men landing not on the moon, but in mega-mushroom country, to excerpts from hoary forties-era Campbell’s Soup Kids’ cream of mushroom soup commercials, to stunning time-lapse photography showing the birth of bulbous white ’shrooms in extreme close-up, the film is something out of a stoner’s dream. And yet, it’s grindingly but still entertainingly informative, both showing and telling us everything we’d ever want to know about the tasty little devils. (Factoids: There are 485 species of them used around the world. Enoki mushrooms are proven cancer inhibitors. Oyster mushrooms consume oil, and are used in San Francisco to clean up oil spills.)

We also take a ’shroom-hunting hike with “the Indiana Jones of mushroom hunters,” and visit the annual Mushroom Festival in Telluride, Colorado (which the film opened in 2007), where latter-day flower children parade in tie-dye, waving banners and smiling beatifically. As the credits roll, we are soberly assured in bold black and white with a final, sixties-socially-conscious (but 21st- century suit-conscious) sign-off: “No hippies were harmed in the making of this movie.”

No More Smoke Signals

Smoke of another kind is the backdrop for a Swiss film on the plight of Native Americans in No More Smoke Signals (Fanny Bräuning, 2009), which won several Best Documentary awards and screened at the New York branch of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian a week before arriving in Munich. Set in the barren hills of South Dakota, Bräuning’s deeply felt and provocative documentary was inspired by an assertion from her 5-year-old daughter, who informed her that the United States was settled by “people and Indians.” Concerned, Bräuning hastened to assure her that Indians are also people. “No they’re not,” returned the child. “They have feathers on their heads.” Unfortunately, that misperception is not limited to Swiss children.

No, Native Americans do not have feathers on their heads, nor do they send smoke signals. What they do, at least the Oglala Sioux nation on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, is have a radio station. “Kili Radio – The Voice of the Lakota Nation,” is the common source of news and information linking old and new, senior and young, tradition and progress, past and present. But while it joins them, it also divides them. The world is interconnected, observes a woman — “I can put something on eBay and someone from New Zealand will buy it,” she marvels — but not everybody is ready to buy in, out of fear of the new, or of losing touch with their roots: “Lots of people don’t want that.”

What they want, says the outspoken American Indian Movement (AIM) activist Leonard Peltier, is respect, and justice. (Peltier is currently serving two hotly debated consecutive life terms for the murder of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in 1975. According to the press notes, 60 members of Congress, the European Parliament, the Dalai Lama, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop Desmond Tutu, among others, have pleaded unsuccessfully for the case to be reopened. Bräuning would express surprise at one of Filmfest München’s intimate “podium discussions” that so few Americans know of Peltier or his work. Peltier was again denied parole in late August.)

While No More Smoke Signals is technically a documentary, the film’s score is highly cinematic, sweeping us into the arid magnificence, the canvas of gold and red earth of the Dakota plains. The people live in poverty — of the reservation’s original 150,000 square miles, only 5,600 remain; per capita income hovers around $6,000 and unemployment is near 90% — but they are fiercely proud of their heritage and are determined not to forget, or let the rest of the world forget, their tragic history. The Wounded Knee Massacre of a century ago, in which a misunderstanding led to the slaughter of some 300 Lakota Sioux men, women and children by the U.S. Cavalry, is still fresh, and its legacy lives on in the blighted lives of many who struggle with alcoholism and depression. Yet there is originality and creativity, and hope. We meet Derek Janis, a tattoo (and tattooed) artist and musician who regularly broadcasts his skillfully woven Native American chants and African American rap on Radio Kili (“I think it’s kind of cool,” an elderly woman told the director during filming), a constructive alternative to petty larceny or getting drunk (there being not much else to do on the Reservation).

And then there is the indomitable Roxanne Two Bulls, the mother of eight children fathered by four abusive men who has been dragged down repeatedly by addiction and alcoholism, only to bounce back by dint of her own strength and courage. Roxanne has found a home on Kili Radio, which she helped found (her show is so popular they have to cut off the phone lines to stop the calls). At the first screening in New York, Bräuning told us, Roxanne laughed — “You got us perfectly” — but cried the second time, homesick for her land and people. Or Buzi Two Lance, who started out as a volunteer and now serves as programming director. Living at peace in two worlds, he is equally at ease soldering cables or explaining his belief that a feather atop the antenna works as well as a costly lightning conductor.

At the post-screening Q&A, Bräuning was asked how Americans react to the charge of genocide implicit in the film. Not surprisingly, they are generally nonplussed (an excellent word here in that both meanings apply, depending on the person in question). “They’re totally blind to it, so far from reality,” praising Native American jewelry, art and other touristy souvenirs and reflexively blaming the Indians (drunk, lazy, unwilling or unable to live in the modern world), reluctant to confront the possibility that the “white man”may be at fault. Indeed, she was warned in New York that she might have to deal with hostile reactions from people offended by the implication that the United States might have something to answer for. But Bräuning (who worked on the film for 6½ years: “The Lakota call this ‘Indian time’; things take as long as they take”) felt that her outsider status allowed her to approach the project without prejudice or preconception.

Lymelife

That said, at times there can be advantages to being an insider. “I came of age in the early ‘90s,” said director Derick Martini in an unattributed interview of his film Lymelife (USA, 2008), a star-studded semi-memoir co-scripted with his brother Steven. The film won the FIPRESCI Prize for Discovery in Toronto last year. “I just grew up amid the ruins of Rome. There was this economic boom where people in the lower middle class were able to move ahead rather quickly. All of the families had problems, everything was falling apart, and what was always nagging at me was, why? Why? Why?” In this star-studded but unpretentious and deeply felt exploration of the suburban dream gone haywire, Alex Baldwin, Kieran and Rory Culkin, Timothy Hutton and Jill Hennessy play people caught up in the maelstrom of pretension, confusion, and frustrated expectations.

“They say wherever you are on Long Island, you can always hear the train,” the beautiful brunette neighbor, on whom he has a major crush, tells our teenage narrator. “You can never get away.” An interesting juxtaposition: imprisonment in the abstract by a vehicle of departure, which for most people is a tangible symbol of freedom. So begins this coming-of-age film as it portrays through his eyes the coming-to-terms with life’s contradictions and betrayals that is a painful if inevitable part of growing up, and the lacerating, often hidden wounds they leave. At its end, the fragile falsehoods that held relationships together will be exposed, and childhood’s implicit faith in the trustworthiness of the adult world will be shattered. Derick Martini’s urgent “why” may still go unanswered, but his compulsion to ask it, and his skill in portraying it, make it a question that reverberates long after that last train whistle fades.

Michael Haneke

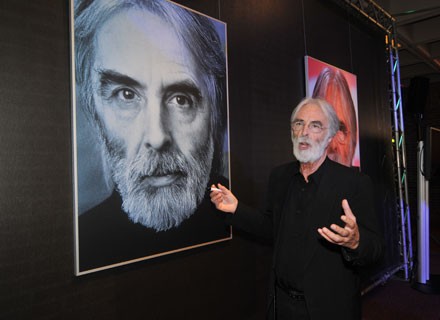

Photo of Michael Haneke from the Munich Film Festival website.

There were plenty of questions at Filmfest München, and many of them were asked not at Q&As or podium discussions, or even at Berlinale-style press conferences — Munich is far too informal for that — but at open-to-the-public “interviews” in the intimate Black Box theatre at the Gasteig. This year’s featured two internationally renowned directors, both of whose films have found favor not just in the U.S., but specifically with DC-area audiences.

Bavarian-born director (and thus native son) Michael Haneke, fresh from a heady Palme d’Or win at Cannes for Das weiße Band (The White Ribbon), who may be best known to Washington audiences for 2005's Caché and 2001's The Piano Player; was this year’s CineMerit Award recipient for “extraordinary contributions to motion pictures as an art form.” And DC’s arguably favorite British helmer Stephen Frears was the subject of this year’s Filmfest München Retrospective. Two more different directors could not be imagined. The same could be said for their personalities onstage — although not quite in the way that might be expected.

The real stunner was Haneke, whose dark and brooding and often violent films and grim press-photo countenance seemed to presage an equally bleak or even brutish hour. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Clearly at ease in his hometown, greeting the packed hall with a warm smile and friendly eyes, the director was expansive in responding to questions from both his hosts and members of the audience.

The interview began with a comprehensive overview of Haneke’s career, then segued into a discussion of his films and influences. At the suggestion that the latter might include his filmic forbear and fellow Bavarian Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Haneke replied to the surprise of many that he’s really not much of a Fassbinder fan. The enfant terrible cum wunderkind of the New German Cinema (who was a great admirer of Douglas Sirk’s social dramas, but whose own films, like Haneke’s, did not shy away from violence) is for Haneke “too sentimental.”

To be sure, that’s an accusation that could never be placed at this director’s doorstep. Asked about the scene in his horror thriller Funny Games (2007) where the murder of a child is drawn out for five excruciating minutes (“nope, ten"), its impact intensified by the agonized groans of the parents, Haneke deflected the implication by noting that there was a four-minute scene in another film that was “the talk of Cannes,” adding that his own filmic violence is generally not onscreen and in-your-face. “You have to leave room for the audience’s imagination to fill in the blanks,” he said. “The anticipation is worse than the realization.”

The White Ribbon, scheduled for a limited U.S. release on Christmas Day and rumored to be Germany’s submission for 2010's Best Foreign-Language Film Oscar (it also won the FIPRESCI Grand Prize 2009 for Best Film of the Year at the end of August), leaves plenty of room for the audience’s imagination, and does so in a way that is elegant, measured, and chilling. Set in a deeply religious northern German town at the close of the First World War, the film, shot despite the producers’ unease, in a time-appropriate black and white, has been seen as a commentary on the psychological mindset that allowed the Nazis to come to power. But Haneke was quick to caution this as too simplistic a reading: “There’s a fascism of the left and of the right. Any ideology can become absolutist if you take it to its extremes.”

That said, it is an über-rigid, repressive and unforgiving right-wing ideology that warps the hearts and minds of many of the inhabitants of this village and, as night follows day, will twist those of their progeny. But as they do not see it in themselves, they will remain blind to it in their children. Until it is too late.

In an interview with the newspaper Abendzeitung, Haneke, told that his films “leave us sitting there alone with lots of questions,” agreed. “The job of art is to raise questions, not to provide answers. Answers don’t get you anywhere. Questions, on the other hand, can help sometimes. That’s the principle of my films; they function as a ski jump. The viewer has to do the jumping himself.” And the violence? Haneke is “not a fan of guilt or violence, but they characterize our world and you can’t get away from talking about them. Dramas are for portraying conflicts, not idylls.” As difficult as his films may be for some, Haneke, in the words of actress Susanne Lothar, presenting the laudation at the CineMerit Award ceremony, “approaches the basic questions of life with humility, humanity and determination. He has the highest respect for the feelings of the audience.” Humility, in spades. As the director told Abendzeitung when asked about the paucity of music in The White Ribbon: “I don’t need a soundtrack. Music is too important to me for it to be used to hide my mistakes.”

$5 a Day

On the other side of the moral spectrum, hiding his mistakes is second nature to the aging but infuriatingly, delightfully incorrigible con man Nat Parker, played to a T by the protean Christopher Walken in Nigel Cole’s $5 a Day (USA, 2008). Nat is a supreme charmer who’s the bane of his beleaguered son’s existence — when we meet Flynn (Alessandro Nivola), he’s lost his girlfriend because he’d told her his Dad was dead, making it somewhat inconvenient when Nat calls to tell him he’s actually dying. Which, knowing the sly old fox as well as he does, Nat doesn’t buy for a minute. Nonetheless — just in case, on the slightest chance that this time, for once, it’s real — he lets himself be talked into driving X-ray-laden Pops to Mexico for an experimental, potentially life-saving treatment.

In classic road-trip movie style, the two travel the back roads of America (in a candy-pink convertible bearing the Sweet ‘n’ Low logo, which Nat acquired in one of his “deals”), meeting a panoply of off-the-wall characters whom Nat sequentially sweet-talks and defrauds, as often as not with the victim teary-eyed with sympathy, affection or gratitude as he exits. The less-is-more ethos that’s become increasingly attractive for some and a necessity for others makes him almost a hero to the hard-up, his motto “Everything’s free” irresistible to those for whom everything has suddenly become (or has always been) out of reach. This happy philosophy, however, cannot help but grate on his son, who served hard time in prison after getting unwittingly caught up in one of his father’s schemes.

There are some priceless vignettes, with plum perfs by Sharon Stone (as the classic whore-with-a-heart-of-gold), Amanda Peet and Peter Coyote, in addition to those of the two leads. And some of the one-liners are sure to evoke knowing if rueful nods, if not screech-level fury. Asked by his son if he really loved the son’s late mother, Nat tells him, oblivious to the pain it will cause: “You know what women are like. You say it in the heat of the moment, they think it’s forever.” But the sandpaper relationship between father and son gradually loses much of its roughness as the two are forced to see each other up close and personal, and begin to work through the accumulated resentments and misunderstandings that have, rightly or wrongly, kept them at arm’s length.

The Day Will Come

Distances, misunderstandings and one-sided resentments dividing parent and child have also accumulated in Susanne Schneider’s emotionally draining but potent Es kommt der Tag (The Day Will Come, Germany/France, 2009). As it screened in Munich without subtitles, your reporter did not foresee writing it up here, assuming that it was destined solely for European distribution. Not so: If you plan on being in Toronto this month, you’ll find that it’s part of the line-up at TIFF 2009; so a brief recap is in order.

The negative feelings between child and parent are considerably stronger here, the back story appreciably more intense, and involve not father and son but mother and daughter. Having discovered that the people who raised her are not her parents, Alice has done some spade work and learned that her mother was a member of a terrorist group in the 1970s (think: Baader-Meinhof), served time in prison for the murder of a bank guard, and has been living in a nearby town without anyone being aware of her past.

For Alice, the matter seems simple: Expose the woman’s deception, identify yourself as the child she selfishly threw away so she could pursue her iniquitous, criminal lifestyle, and rid yourself of the hurt, the feelings of rejection and betrayal, that have not allowed you a moment’s rest since you learned the truth. For Judith, except for being haunted by the memory of the little girl she entrusted to the care of friends 30 years before, the past is dead and buried. Now married to a kind man with whom she has two teenage children, none of whom has any idea of her past life, at the time she believed the sacrifice necessary to allow her to pursue her misguided dreams of, as she saw it, making the world a better place by violently ridding it of those deemed institutionally or individually responsible for its misery.

The film does not take sides; the viewer feels a measure of sympathy and anger toward both women, each of whom is portrayed with conviction (the daughter’s righteous passion is chilling, the mother’s resignation, eyes filled with memory and acknowledging defeat, heartbreaking) and for the untenable situation in which they find themselves. In the end there will be a grudging coming-to-terms with each other’s reality, but in far from Hollywood-feelgood fashion. “Reconciliation between the generations — between the fighters against injustice and their apolitical children — remains, as the film suggests, a utopia,” writes German critic Joachim Kurz astutely in Kino-Zeit (Movie Time). “In film, as in reality.”

From Mother to Daughter

For the women in Andrea Zambelli’s delightful Di madre in figlia (From Mother to Daughter, Italy, 2008), reconciliation is not an issue. These twenty mothers and their twenty daughters are bound not only by maternal and filial affection, but by a mutual love of music — to be exact, singing. In a tradition forged in the rice paddies, familiar to film scholars from the classic Riso amaro (Bitter Rice, Giuseppe De Santis, Italy, 1950), the madri — as the choristers in last year’s smash hit Young at Heart, now in their seventies and eighties — and their figlie travel around the world singing the ballads, pop tunes and protest songs that kept the mothers going as they performed backbreaking work during the desperate years of the second world war.

Despite their ages and the difficulties of their lives they haven’t lost a bit of enthusiasm or stamina, and the joy they find in living (and singing) is evident in the smiles on their faces and the intimately affectionate teasing they engage in. Eager to share their music, the ladies are intrepid world travelers. One of the most enjoyable parts of the film recalls their visit to Detroit in the summer of 2007. As singing seems to come to them as naturally as breathing, it isn’t long after boarding a tour boat that they strike up a song. Watching the other passengers react is like seeing an episode of the old TV show Candid Camera: first puzzled, then curious, then amazed, gradually about half the deck — black, white, hispanic, Asian, Native American — start clapping along, beaming with pleasure, developing a rousing, rhythmic accompaniment ending in cheers and applause.

While two more different films and kinds of life experiences could hardly be imagined, as the women in My Neighbor, My Killer, those in Di madre in figlia have come together to remember a shared past. An odd comparison to be sure. But the shock of seeing these two films, by sheer coincidence, one following the other accentuated their superficial similarities, and may have allowed a viewer’s feelings of helpless disbelief, which stayed just below the surface during the first film, to find release in the second. Though their common motto may be “Do not forget” (one waited in vain for the Italian ladies to warble the beloved Nat King Cole classic, “Non dimenticar”), it is remembrance of another kind that binds this remarkable chorus of singing seniors. Lifting their voices, still astonishingly strong and resonant, in tribute to their youthful victory over pain and want (and now, over the ravages of age), they affirm in ringing tones the resilience of the human spirit.

Tahaan - A Boy with a Hand Grenade

That quality is pre-eminent, but its holder the junior of those ladies by about three-score years in Tahaan (Tahaan – A Boy With a Hand Grenade, Santosh Sivan, India, 2008), part of the Kinderfilmfest (children’s film festival) slate but arguably a shade too complex and sophisticated for young children. While the boy himself may have seen sixty fewer summers than the women, the habitually erupting conflict in which he becomes ensnared is quite their contemporary. Eight-year-old Tahaan lives with his mother, sister and grandfather in Kashmir, a vast area bordered by India, Pakistan and China about six times the size of Maryland with a little more than twice the population, whose location has made it the object of territorial claims by all three nations since 1947. The father has been missing for three years, leaving them at the mercy of the local moneylender when the grandfather dies. That Dickensian villain promptly seizes all of the family’s assets, including Tahaan’s beloved donkey, which the boy immediately runs off to reclaim. His journey is the heart of the film.

While the story seems simple, its realization is anything but. It may sound hyperbolic to say that the director, the screenwriter and the cinematographer seemed to work as a single unit, but in this case it would be no exaggeration: Santosh Sivan served all three roles. Tahaan’s world is filled with poverty and injustice, but the wisdom and love he has absorbed from his family give him the acumen and fortitude not just to pursue, but to occasionally outwit his older and shrewder adversaries. The elderly grandfather’s edifying fables, which no doubt have their origins in folklore, are illustrated in luscious, breathtaking images of the natural world that take on new meaning when they are followed without pause by a gloomy shot of the grandfather’s body. It is such incomprehensible contradictions (including American tourists losing their way in sparkling convertibles trying to find reception in the primitive area on designer cellphones; a deeply empathetic and honest-looking young man who risks life and limb to help Tahaan — only to betray him in the end) that make up the boy’s world.

Samson and Delilah

In Australian director Warwick Thornton's Samson and Delilah (2009), the young people’s poverty, rather than being alleviated by the care and concern of a loving family, is instead exacerbated by the ignorance, cruelty, and stinging rejection of a primitive and equally impoverished society.

We find ourselves in a deserted wasteland in every sense of the word: scarcely a soul to be seen, wild dogs roaming a parched, trash- and garbage-strewn earth shrouded by a cold, insensate silence. Yet two teenagers who live in this outskirts of an aboriginal community, and whose lives we will come to share, have not yet been irreparably damaged by its brutality. Each is sustained by a love for something that allows them to reach beyond the bleakness of their lives: she, by pointillist paintings, which she creates with carefully hoarded canvases and cherished tubes of paint; he, by playing in a loudly percussive band whose members swear violently and otherwise try to discourage challenges to their authority. But they are unaware of the strength and unpredictability of their lanky, childlike, silent new colleague, and when they repeatedly disturb his sleep with their cacophony to a point past human endurance, his splenetic reaction is swift and lethal.

Oh yes: neither Samson nor Delilah speaks. But the poetry of their eyes and limbs, as filmed by Thornton, is more eloquent than speech. Poetry does not pay the rent, however. And when Delilah’s beloved grandmother dies, and Delilah is unjustly held responsible for her death and beaten bloody by angry neighbor women — and Samson takes revenge by going on a violent rampage, destroying everything in sight — the two join in a desperate flight from the only life they have known. The world beyond their borders is strange and full of wonders, but the dangers for two innocents are no less menacing.

At a Q&A following the screening, Producer Kath Shelper conveyed Warwick Thornton’s regrets for being unable to attend, explaining that the director (an Aborigine himself) was at work on a projected 3-hour documentary on Aboriginal art. Thornton, we learned, had initially planned on being a DP and even completed a degree in cinematography, only to find that he had “no gift for self-promotion.” Weary of waiting for offers to come in, he decided to just go for it and make his own films; Samson & Delilah is his first feature (the preceding four were shorts), making his Cannes “Camera” an even more remarkable achievement. (It is also the highest-grossing Australian film so far this year.) Fame hasn’t changed him, though: He still has no cellphone. And then there’s that other concession to civilization that Thornton hasn’t made, and that makes his achievement, while still remarkable, seem almost ineluctable: a DP to the marrow of his bones, Thornton “can read and write, but not very well. He thinks in images.”

A Shine of Rainbows

All cinematographers would no doubt lay claim to the second part of that description, although the gift seems more striking among those who likewise wear the director’s hat. Strikingly, another film that also connected the DP-director dots bears additional similarities to the preceding two. As with both Tahaan and Samson & Delilah, A Shine of Rainbows (Canada/Ireland, 2009) is by a non-U.S. filmmaker from a country where English is spoken and understood by most of its citizens; as with the first, it was a surprisingly sophisticated (but more easily accessible) Kinderfilmfest offering by an Indian-born director; and as with the second, it is by a director-cinematographer who also has roots in Australia. While this deeply felt and superbly photographed film has received astonishingly little press, the same cannot be said of its director-DP (and co-writer) Vic Sarin, whose vita includes four award wins (including two Emmys) and another 14 award nominations, as well as a Kodak Lifetime Achievement Award.

It begins like a fairy tale: Tomás, a small, redheaded eight-year-old with a speech impediment, lives in a Catholic orphanage where he is the object of taunts and treachery by his older, tougher, shrewder schoolmates. One day, without warning, he is whisked away to a faraway island by a beautiful, cheerful, lustrously redheaded woman who has decided to adopt him. And they lived happily ever after, cue titular rainbows, end of story, right? Not quite: like any child’s in a fairy tale, Tomás’s happy ending will come only after his princess has been rescued and his dragons slain. But these archetypical fairytale victories will be realized at a very adult, real-world cost. And along the way, several lives will experience a sea-change. The dragons will turn out to be complex creatures whose fiery breath is a pre-emptive shield. And the princess’s magic wand will transform his world by showing him how memories held close can be his own shield against loss; and how a rainbow’s true magnificence lies in its quiet victory over rain.

Father of My Children

There is no such victory in this year’s Cannes Special Jury Prize – Un Certain Regard winner, Le père de mes enfants (Father of My Children, Mia Hansen-Løve, France, 2009), whose director drew inspiration from the life and tragic suicide of film producer Humbert Balsan, for years a powerhouse in French and Middle Eastern film. Hansen-Løve, a former critic for Cahiers du cinéma, had more than a tangential, critic’s connection to Balsan: among the numerous projects he had under development when he died was a script she had penned.

The film was important for Hansen-Løve to make “not just because he wanted to produce my first film, not just because he was such a special person, such a beautiful person,” she told the audience before the screening, but because of his impact on French cinema. As we saw in last year’s What Just Happened? (Barry Levinson), a producer’s life is a never-ending stream of impossible suggestions, requests, demands and musts, pick-ups, hang-ups, drop-offs and drop deads, with — if he’s lucky — a few quiet moments with real human beings (otherwise known as “family”). But where Levinson’s film was a romp through the DDT-laden garden of Holly-weed, Hansen-Løve’s is a tribute to the multi-tendrilled vine caught in the crossfire, too fragile and overextended to sustain the blast.

From the get-go, we are plunged head first via agitated hand-held into the pressure cooker of a producer’s life, cellphone a permanent appendage, fielding and making calls and connections at lightning speed while obliviously navigating (or not) the perils of equally oblivious city traffic. Our producer is plagued by a particularly nettlesome production by a Swedish art-house filmmaker — some might call him a visionary or maverick — in whom he believes but whose endless films, while reaping critical praise, are reliably DOA at the box office. (At the time of his death Balsan was trying to obtain financing for a film by the Hungarian director Béla Tarr.) Negotiating unremittingly with money men, using every ounce of persuasion he can muster and scraping the bottom of his personal barrel, he refuses to let his friends help him, is too proud to go to his wealthy family, and keeps his wife and children in the dark, not wanting to worry them. A supremely decent and honorable man, and one with both a passion and a vision for film and all that it can be — pretty much the antithesis of the classic producer images on which we’ve been weaned.

As he sees it, there is no way out: Too many promises made that can’t be kept, too much time and money spent on a project that can’t be finished and is sinking ever deeper into disastrously unpayable debt. Too much pride, too much shame — “I’m a failure,” he tells his sympathetic, intelligent but ultimately helpless wife; too much love for his daughters, the eldest a moody, contemplative teen, the younger too feisty and adorable — to be able to look them in the face anymore. And so he does what he feels he must. The scene is handled with great delicacy and respect; we see nothing but his solemn resolve, and intuit what happens next. The second half of the film portrays the aftermath with a mixture of sensitivity tempered with a businesslike insider’s acumen, as the family attempts to sort out the emotional, professional and financial ramifications of his death.

“The important thing [in making the film] was not to focus on what was lost with his death, but what he left that will live on,” said Hansen-Løve. “This man was more than just a producer; he was an artist, not only through his work but through his character and his humanity. He should not be forgotten.”

Henri-Georges Clouzot's Inferno

Films and people who should not be forgotten were a particular focus at this year’s Filmfest München. A spectacular example — one that also coincidentally came straight from Cannes, was a French film, and concerned a celebrated French filmmaker who suffered from serious depression (although in this case a more clinical one) — was L’enfer d’Henri-Georges Clouzot (Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno, Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea, France, 2009). Long-lost footage of the legendary last, but never completed film of the “French Hitchcock” perhaps best known for Diabolique (1955) and Wages of Fear (1953) has been recovered and appears for the first time in this revelatory documentary. (Note: it will screen at TIFF this month.)

Introducing the film, director/producer Serge Bromberg told of a chance encounter in a stuck elevator with Clouzot’s widow, who told him of the footage: 185 cans of film, 13 hours in all. As the magnitude of this information sank in, he rang her up and asked whether the material could be screened. No, she told him, citing legal rights and other matters. Eventually they came to an agreement, and the images, “more mind-blowing than the legend predicted,” form part of a startling film that hints at what would have awaited film buffs had Inferno been completed.

The title of the documentary is itself revelatory, in that Clouzot’s “inferno” was not simply in name only. Nor did it stop, as did Balsan’s, with him. While every film has its behind-the-cameras back story, L’enfer, whose filming Bromberg calls “cursed,” is among those few in the history of cinema in which the director’s obsessive perfectionism ensured that the film whose hallucinogenic special effects so closely mirrored his own psychological state, remained unseen during his lifetime. “Clouzot wanted to explore the feeling of anxiety he had every night, but it would take too long to present what built up over a lifetime in a person’s mind,” Bromberg told us. It did indeed take too long to finish the film. But what Bromberg and Medrea have put together from its long-lost images, hidden away for half a century, allows us a harrowing look into those that must have filled Clouzot’s tortured dreams. And their interviews with surviving cast and crew members take us inside the set that formed the backdrop for their filmic realization.

We see Costa-Gavras recalling the careful attention Clouzot, “one of the true greats of French cinema,” gave to a suggestion Costa-Gavras offered for one of the scenes, studying it for a full 10 minutes so as to envision how it might work best. The film, we learn, was written for the young film star Romy Schneider, who had come to the attention of critics in Orson Welles’s The Trial (1962). The screen tests we see testify to her beauty and magnetism, as well as to her willingness to be put through the wringer, as Clouzot was wont to do. The other actors were less patient: Serge Reggiani, who plays her obsessively jealous husband and was selected for having “the face of a carved chestnut. Perfect for the role!” would leave after three weeks of being “tortured” by Clouzot. We are shown a meticulously detailed chart with hundreds of entries in which each of the hero’s moods is color-coded (even more impressive when one considers it was pre-PowerPoint and done entirely by hand). Chastised for his detailed planning by his young compatriot colleagues, the New Wave directors who had burst upon the scene in the late 1950s with a zest for improvisation, Clouzot replied: “I improvise on paper.”

But obsessive perfectionism has its costs, not just to those who are its targets, but to those who must keep reloading again and again, never satisfied with less than a perfect bull’s eye. In a scene where Schneider and another woman are locked in a passionate embrace, Clouzot approached to give the women direction, and collapsed. “It came at the right time,” says Catherine Allégret, who played the role of Eve. “He could not have gone on much longer.”

You Will Be Mine

Women locked in passionate embraces, French film and not being able to go on any longer bring us almost irresistibly to Je te mangerais (Sophie Laloy, France, 2009). The film’s English title in Munich was the anodyne Emma & Marie, which Laloy didn’t like, and no wonder: A more literal translation would be the wolfish “I will eat you up.” Because that is precisely what Emma would like to do to Marie, (Variety uses the more subtly menacing You Will Be Mine.)

The two are piano students at the Lyons conservatory, childhood schoolmates who haven’t seen each other in years. Marie, a vivacious brunette, decides that sharing her parents’ apartment with a fellow student will save needed money, and Emma, shy, pale and something of a loner, sees the mutual advantage and agrees to move in. “You seem different,” Marie tells Emma when she enters the apartment. “Maybe it’s the way you do your hair up...?” “Is that why you didn’t call me?” Emma responds sharply. And we’re off.

The tension is palpable, and to an extent understandable, as most students in the performing arts would no doubt attest. (The director studied piano at the age of 17 at the Lyon conservatory where she lived with another student: “Our relationship was full of unspoken things.”) An uneasy mix of fierce competitiveness and you-go-girl encouragement develops between the two, with Emma at one point assuming the role of protector when the more naive Marie is hit on in a bar and almost raped. “Your sweet, sparkly nature is great, but guys see it as a come-on, that you want it,” Emma instructs the traumatized Marie. A reassuring hug slowly slides into a sexual embrace, and Marie (who has now in effect been assaulted twice in one night) bolts.

But Marie’s initial fear and revulsion will turn to curiosity, and the two sleep together. Emma takes this as a sign that Marie has accepted her as her lover and guardian and becomes fanatically protective, embarrassing her at one point by railing at their teacher when Marie, unable to practice because her life has turned topsy-turvy, fails to place in the competition. Realizing that things have gone too far and unable to reason with Emma, Marie announces she’s moving out. And that’s when things get really nasty.

Threaded throughout this psychosexual drama are scenes seemingly cut from the pages of a memoir that capture the human side of conservatory life and competition. One that stays in the mind is the close-up of a young man intently watching his performance on television with friends and fellow students. His reactions — from shy embarrassment, to meticulous, riveted attention to each note, to quiet pride in which can be read a history of hard work, hopes, dreams and disappointments, with a flicker of sweet victory — is so real, it’s hard to believe that this is an actor. And the music, from Bach to Schumann to Ravel to (an uncredited) Schubert, sweeps the viewer along to a place where film and music at last find common ground.

Cinema in Concert

Music and film also found common ground in the exhilarating special program that opened Filmfest München, “Cinema in Concert: Filmmusik Made in Munich.” Emceed by actress Maria Schrader the program, featuring excerpts of scores from films either scored or produced in Munich, made exciting and imaginative use of cinema techniques in a theatrical setting. Three huge, white floor-to-ceiling rectangular panels placed at equal intervals across the rear of the stage served as screens across which scenes from each film flowed, hypnotically melding into, then superimposing each other. Or kaleidoscopically filter-altered video shots of the musicians (or selected parts of them, sometimes enlarged or miniaturized beyond recognition yet artistically rendered) as we watched them play. Talk about divided attention: One’s eyes went from screen to screen to screen to stage, not knowing where to look first, while being irresistibly lifted out of one’s seat by the music.

The music was provided by the Münchner Rundfunkorchester (Munich Radio Orchestra), its conductor so passionate and precise he effortlessly sprang three feet off the podium in the opening number (the overture to the popular and long-running German television series“Tatort,” or scene of the crime), swiftly slicing his baton through the air like a just-sharpened sword. Their thrilling rendition of Alberto Iglesias’s rousing, emotional score to Pedro Almodóvar’s Oscar-winning Hable con ella was Hispanic to the roots of its soul, tempting one to look around to be sure we were still in Germany.

Actress Maria Schrader (who is very popular there but less well known here; DCFS members may have caught her in Margarethe von Trotta’s Rosenstraße, which screened here a few years ago), lovely and elegant in tiara and satin gown, briefly described the films, their plots, and their backgrounds. She also spoke eloquently of the importance of music in expressing things in film that cannot be seen or spoken, in opening hearts and broadening minds. These subjects were also taken up in a half-day program offered in connection with the concert: “film, sound, style,” whose sessions included such topics as “Film music as emotional strategy,” “The sound of pictures,” and “Music — blood or heartbeat of a film?”

Kisses