The 58th Berlinale

By Leslie Weisman, DC Film Society Member

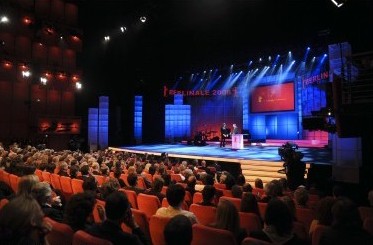

The Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) is known for offering a glam red-carpet venue, and its attendant cachet, for high-end film product and internationally recognized talent. This year’s Berlinale filled the bill spectacularly, anticipating the Academy Awards by a week in awarding two Silver Bears (Best Director and Best Musical Score) to the subsequent two-time Oscar winner There Will Be Blood. Last year’s Bear fest also was a jump ahead of the Oscars, opening with La vie en rose, for which Marion Cotillard won this year’s Oscar for Best Actress.

Opening night at the Berlinale

This year’s Berlinale was anticipatory in another sense, screening films that would hit DC cinemas on the heels of their Berlin premieres, among them Be Kind Rewind (the closing-night film) and The Other Boleyn Girl, two films which were otherwise as unalike as Jerry & Mike and King Henry VIII. Commonality resumed as the stars of both films took to the Berlinale’s press conference stage in the Hyatt to wildly enthusiastic applause, exceeded only, perhaps, by the ovations accorded Madonna and Martin Scorsese (the latter sharing the podium with The Rolling Stones, featured in his latest film, Shine a Light), who also were on hand to promote their respective movies. More on that later; first, for a bit of perspective, some numbers.

With some 430,000 festival goers, including more than 20,000 accredited visitors from 125 countries attending nearly 400 films shown in over 1,250 screenings, the 58th Berlinale surpassed all previous records. (To give an idea of the fest’s size, the screenings were spread among 14 cinemas with 71 screens, of which 47 screened festival films.) Parallel to, and at times sharing talents with the festival was the sixth annual Talent Campus, which this year featured more than 80 events with 150 film experts who gave generously of their time and expertise to several hundred up-and-coming international filmmakers. The roster of experts included distinguished directors and stars whose films or roles had been recognized in previous Berlinales, or which were being screened in one of the festival’s venues and would later win a coveted Bear at this year’s closing ceremony.

Having regretfully passed on the Martin Gropius Bau’s special series, “Eat Drink See Movies – Celebrating Culinary Cinema” (with fond remembrance of my first visit there for the delightful Sideways and its wine- and lecture-filled dinner), I found my regrets slowly transformed into gratitude, as I watched the debut feature film of a former Talent Campus participant: Lance Hammer’s Ballast (USA, 2008). Fresh from snatching Sundance’s coveted Directing Award: Dramatic, and Excellence in Cinematography Award: Dramatic only two weeks before, Ballast won over the local critics as well, who praised it for its bleak but powerful depiction of the lives of an African American family in the Mississippi Delta. “An aesthetic as experimental as it is assured... breathtaking for a first film,” wrote one. “Golden Rule for the Berlinale Competition: the less a film strives for, the more it achieves... in a few scenes lie an entire cosmos,” observed another.

Serendipitously mirroring that evaluation, the press conference was filled with illuminating contradictions. Director Hammer allowed that the film may seem improvised, perhaps reflecting the influence of French filmmaker Olivier Assayas and others he admires, but emphasized that it is a very American film, whose script he spent two years writing. And yet... it was important that information in it be revealed slowly and not spelled out, something that is rare in American movies. “In our lives we piece together reality gradually, so why not in films?” But then... “We were aiming for a sense of immediacy,” said cinematographer Lol Crawley of the hand-held camera he used. “You felt you were reacting with your heart.” When it came to the actors, they were left to develop some of their own dialogue, after getting a sense of their characters. “If you live in the Delta, you live with drugs and crime and poverty,” said actor Micheal J. Smith Sr., who had never acted before, “so it was a natural collaboration” with Hammer.

Indeed, Hammer was intent on not using professional film actors, looking for “emotional truth” (“I subscribe to the Robert Bresson school of casting”). Tarra Riggs, whose memorable portrayal of mother Marlee is the emotional heart of the film, has done some theater work; however, even she credited natural methods — “Like reading a book: each page brings out a different emotion”; with only a minute or two to react between reading and shooting a scene, “I used what I felt in my head” — with being key to her ability to bring the character so vividly to life. The fact that the people they play are so different from their own personalities (“I’m usually a bubbly-type person,” said Riggs, while Smith had to go back seven years to his son’s heart surgery to find his character Lawrence’s lugubrious depression and need for solitude: “I’m not a silent, depressed kind of guy”) made the roles especially challenging and even rewarding for them.

Regarde-moi (Ain’t Scared, Audrey Estrougo, France, 2007), on the other hand, challenges the audience, straight-up and close-up. Speaking directly into the camera, an ebony-skinned man simultaneously seduces and threatens the viewer, telling you how hot he is, how much you want him, and what his plans are, should you fall into what he no doubt perceives to be his irresistibly honeyed trap. The challenge and seduction are not, however, aimed at you; as the camera pulls back, we see that he is speaking into a mirror, and rehearsing the lines he will use on his next target. The powerful immediacy of this effect is followed by a similarly deceptive, almost heart-stopping shot that takes a 21st-century page from the Lumière brothers: in this case, it’s not a train, but the head of a huge German shepherd, all teeth and eyes, which we instinctively fear and pull back from... only to have him turn and smile, dog-fashion: mouth open, tongue wagging, eyes inviting. Pet me.

These two contradictory images serve as a sort of shorthand for what follows in this street-wise French film by a 23-year-old woman (both writer and director) about conflicts and relationships between the sexes in the Parisian ’hood, which rings so true to a Washingtonian, the only substantive difference is the language the residents speak. (In some cases, this turns out to be a distinct advantage: the slogan “Black and Proud” in French, shown on a girl’s T-shirt, becomes the rap-like rhyme: “Noire et Fière.”) Caught up in its social, psychological, and economic dynamics, we are halfway through the film before we realize we’re seeing the same 24-hour cycle twice: first from the male perspective, then from the female. The sexual dialectic is now echoed by, now played out against the racial; in the end, we are left with a two-sided conclusion which, like the film, eschews the easy way out: the luxury of certainty.

Certainty is also not the first word to come to mind with the second film of another Talent Campus alum, one of Mexican cinema’s most promising young filmmakers — and that goes for both the film and its critical reception. Loved by Screen Daily (“A surefire arthouse bet... Eimbcke is a master of tone”), panned by Variety (“A lazy exercise in minimalist humor”), with The Hollywood Reporter splitting the difference (“...carefully crafted... but it will be mainly fest audiences who have the patience to admire [its] subtleties”), Fernando Eimbcke’s Lake Tahoe (Mexico-U.S.-Japan, 2008) took home the Alfred Bauer Prize, awarded in memory of the Berlinale’s founder for “a work of particular innovation,” and the FIPRESCI prize for Best Competition film. It was also a public favorite, filling the Berlinale Palast’s 1,600-seat theater after most of the pros had gone home.

Why such polarized reactions? Lake Tahoe is a film without an explicit narrative, which may be the key. (Indeed; as International Jury President Costa-Gavras told a local paper, speaking generally, “Nothing is more powerful than the image.”) The story it tells is, in both senses of the word, shown, in episodic fashion, as we follow a young man in his languid but determined search for a part to fix his car, which has crashed into a pole. His quixotic confrontations with the town’s citizens are the heart of the film... or so it seems, until the very end, when the last piece of a puzzle we didn’t realize we were putting together falls into place. And the film’s heart, and the boy’s, are revealed.

Revelations of another kind — with hearts in appallingly short supply — are the focus of Errol Morris’s Abu Ghraib exposé, Standard Operating Procedure (USA 2008). The only documentary in the history of the Berlinale ever to be nominated for a Golden Bear (it was to win the International Grand Jury’s Silver Bear), Standard Operating Procedure takes us behind the prison walls with on-camera interviews of soldiers whose names have become indelibly linked with the prisoner-abuse scandal, along with photographs and footage (recreations) that bring us closer to the “action” than we may ever want to be.

Lynndie England, Janis Karpinski, Megan Ambuhl, Jeremy Sivitz, Javal Davis and Sabrina Harman all sit before Morris’s camera to answer his questions and try to explain how Abu Ghraib happened. The soldiers are forthright and for the most part unashamed of their actions; as England says (in an admission that was almost physically painful to hear, uttered nonchalantly by an American soldier and heard in a nation weaned on the terrible lessons of the Nuremberg Trials), “When we got there, that [the abuse] is what we saw. The example was already set. That’s what we saw. [So we felt] it’s OK [to do it].” She later notes: “You can’t just walk away and say, ‘Hey, I’m not doing this.’ Either way you’re gonna get screwed,” by way of criminal prosecution if one participated, or repercussions from the military brass for failure to carry out orders if one didn’t. Echoing England, a criminal investigator adds tellingly: “It’s ridiculous for these retired officers to say, ‘You should have known these were illegal orders.’ That’s ridiculous. You do that, you get your behind kicked.”

The fact that four of the chief perpetrators were women does not go unremarked; the men, however, are very much there, both by both reference and by inference. Depending on whom Morris asks, the women felt the need either to prove themselves to the men as equals, or to prove their love for them — and, by extension, their worthiness to be loved. Allegedly, the soldiers were given carte blanche to do whatever it took to get the job done. “We were told to do anything to them short of killing them,” says England. Karpinski, on the other hand, comes off as genuinely outraged at the short stick she drew and the consequences of bureaucratic ineptitude, decrying the 1,500 additional prisoners she was sent, to be housed in a space that was already filled to capacity with 500. Of the “nightly round-ups” of “every male on the street,” Karpinski fumes: “If we couldn’t get the guy, we took their kids. ‘Akhbar, we got your kid. Give yourself up and we’ll release your kid.’ I call that kidnapping.”

A criminal investigator takes issue with the public and media huffing and puffing, noting that the things that elicited the most anger and criticism — including the hooded man standing on a box with fake wires wrapped around him, who was told he would be electrocuted if he moved — were standard operating procedure. “That’s what went on in every war... Hey, I’ve been in Desert Storm. This is nothing different. This is SOP.” Chillingly, he adds: “Torture didn’t happen in those photos. Humiliation happened. Torture happened in interrogations. There’s no photos of that.”

At the press conference, director Errol Morris expressed undisguised contempt for the way the entire situation was handled. “Sabrina Harman took the photo of the murder [of an Iraqi] and was prosecuted for taking the photo and embarrassing the U.S. military” because she was shown in a triumphant, thumbs-up pose, and not for anything she may have done to a prisoner. “You’re talking about a world that has gone mad, closer to Bedlam than anything close to democracy. The wrong people were prosecuted,” he added, meaning the low-ranking soldiers rather than those who gave the orders. “All of them were moral people. Yet all of them participated in these acts. These are America’s children — America’s poor children — who enlisted in the Army for economic reasons. It’s a tragedy for Iraq, and for my country. We tried to get rid of Saddam, and wound up miring the whole country in tragedy. These photos forced us to look at ourselves in a new and not flattering way.”

The same could be said for Russians who see the Oscar-nominated Katyn (Poland, 2007), a deeply personal work dedicated to his father’s memory by the esteemed Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda. The film uses newly discovered archival materials to reveal to the world, after nearly sixty years of secrecy, the truth (framed by a fictional story to make it more commercial and thus, more widely seen) behind the massacre of some 20,000 Polish POWs in Katyn forest by Russian soldiers during the Second World War. (The film screened here at the National Geographic in February.)

The story, and the film that might be made from it, had been on Wajda’s mind for many years: his own father had been among the executed soldiers, and his mother had tried desperately to locate her missing husband through the Red Cross, refusing to abandon hope that he was still alive. But political realities made it impossible even to contemplate such a project. It was not until Poland became a democratic state in 1989 that the truth at last came out, followed by the Soviet Union’s admission in 1990 that the soldiers had indeed been shot by the tens of thousands by the Soviet secret police, and buried in mass graves. Using Andrzej Mularczyk’s novel “Post Mortem” as the basis for a screenplay, Wajda began the long and emotionally draining process of turning it into a film.

In Poland, where the film had its world premiere last year, audiences sat stunned as the credits rolled. “Usually, the director feels satisfied when the audience clap their hands,” Wajda told a reporter. “In this particular case, the silence is much more eloquent, and bespeaks how profoundly [they were moved].” When asked how he thought it would play in Russia, particularly with their presidential elections around the corner, Wajda seemed almost to take offense at the suggestion that the film could be seen that way. “This is a film of elegy, a film of mourning,” he said firmly. To use it for political purposes would be to dishonor the memory of those who died, and whose violent, needless deaths had gone unknown and unmourned for more than half a century.

There is but a single death — unknown to all but the immediate family and those with long memories, for whom mourning is by now secondary to the lingering opprobrium left in its wake — in first-time director and acclaimed author-screenwriter Philippe Claudel’s Il y a longtemps que je t’aime (I’ve Loved You So Long, France, 2008). And while here the personal link may be less devastating, because less immediate than in Wajda’s film, it makes for a no less affecting viewing experience in Claudel’s, which won both the Competition Prize of the Ecumenical Jury, and the Berliner Morgenpost Readers’ Prize. (Even at the press screening, more than one of us — who, as journalists, tend to be somewhat thick-skinned about such things, having seen it all, at least in film — could be observed exiting the theater in tears. And the press conference was unique for the number of journos who asked to be recognized primarily to tell the director how moved they were.)

The action unfolds slowly, as we follow what looks to be just another day-in-the-life-of a literature prof, her husband and two little girls. Yet there’s an underlying tension, almost imperceptible, that hints at the gravity of the backstory: the woman’s elder sister, Juliette, with whom she hasn’t communicated in years, has just been released from prison after serving time for murdering her own child — and will be staying with them until she can get back on her feet.

The film is beautifully paced, with each scene carefully composed, snapshot-like, recalling for this reporter Jacques Rivette’s riveting chamber piece from last year’s Berlinale, Don’t Touch the Axe. Initially hooked by the mystery, we are drawn in by the unerring portraits in miniature limned by Claudel’s directorial brush; to the extent that the film must be, in some way, autobiographical...? Yes, and no (spoiler alert! although there’s no U.S. distribution yet): Claudel once worked in a hospital for chronically ill children, and was deeply moved not only by their pain, but by that of their parents: the hidden pain. Is there a “message” that people can or should take from the film? If there is, said Claudel, it is that no matter how close we think we are to other people, or should be by virtue of our relationship, they will always be terra incognita; we can never fully understand them.

These two lessons were brought home to the protagonists of another quasi-autobiographical film, whose provenance is particularly fitting given the subject matter. Israeli-born director Amos Gitai’s French-German co-production, One Day You’ll Understand (Plus tard tu comprendras, also known as Later, 2008), part of the “Berlinale Special” program of works by contemporary filmmakers honored by the festival, deals with the reluctance of a Holocaust survivor (French film icon Jeanne Moreau) to discuss her horrific past with her children. Based on an autobiographical novel by Jérôme Clément, who joined Moreau and Gitai onstage after the screening, Later is an unusual amalgam of drama and educational film that opens the gates to a subject that has been pretty much taboo in French cinema, even 65 years after the fact: the treatment of Jews in Vichy France.

The film pursues a mixture of cinematic styles, beginning with a deft juxtaposition of scenes: the mother, watching the trial of Klaus Barbie, “The Butcher of Lyon,” on TV burns herself on a pot while making dinner; the son, in his office with a table full of papers laying out his family history — which she’s been unwilling or unable to share with him — hears the Barbie trial on radio, and asks his secretary to turn up the volume. When he later mentions the trial to his mother, she deflects the discussion; we subsequently learn that she has never told him about their family: it’s as though they never existed.

In the post-screening discussion, Clément emphasized that the film is not a story about something that happened three generations ago. “It’s a story about the future, a story about silence, about how we talk to our children... Sometimes, to protect the next generation, there are certain things the first generation will not tell them.” Added Gitai, “Cinema is not an illustrative medium; it creates a dialogue. This was a very personal story, and Jérôme Clément was not obliged to make it public.” Moreau, whose reading of the book impelled her to do the film, recounted her own connection to the story. “I was born in 1928. Growing up, inside my school, I saw little classmates with yellow stars, and I saw them disappear... I was so moved by the book, I wanted to do a film of it. And Amos and I work so well together, I knew I wanted to do it with him.” While the French Resistance has gotten much cinematic play, the issue of French collaboration, perhaps not surprisingly, has not. “It’s never too late,” said Gitai.

The same could be said for the characters of another multinational, quasi-autobiographical film by an Israeli director, Amos Kollek’s Restless (Israel-Germany-Canada-Belgium-France, 2008) — although it doesn’t look good for Israeli poet turned New York sidewalk peddler Moshe and his estranged Israeli soldier son, who haven’t seen each other since the father abandoned his son and wife a decade before. Unlike the more genteel, assimilated paterfamilias of the Gitai film, Moshe, while also a child of Holocaust parents, was raised in the Israel of Exodus (1960), where gentility ran a distant second to survival.

The father-son conflict, played out against the vibrancy and occasional violence of New York’s Lower East Side and the sere, dry desert-scape (and lethal violence) of Israel’s West Bank, becomes up-close and personal to both men, with the suicide of the soldier’s mother. Blaming his father and seeking revenge, he flies to New York to confront him, and to make him pay for the years of suffering that drained both mother and son. While the film is in many places “raw” (per the press notes; one would search in vain for a better word), there are several moments of such tenderness and humanity as to render the otherwise unsympathetic Moshe worthy of some understanding, if not affection.

Director Amos Kollek speaks at the Berlinale

Which is all to the point, given the director’s difficult relationship with his own father. Speaking to reporters after the screening, Kollek, half-joking, said his previous films’ focus on women reflected his comfort level with them, and that with this one, “I decided to confront my own conflicts!” And yet there is “a lot of me emotionally in both the son and the father”: like Moshe, Kollek loves America, “the sense of getting away from it all, being who you choose to be”; like Tzach, Kollek felt anger towards his father, a high-ranking public official who had little time for his son, but also “a great deal of love for him.” Restless took the festival’s Prize of the Guild of German Art House Cinemas. The film is dedicated to Kollek’s father, who died shortly before shooting began.

Emotional disconnect between father and child could not be more foreign to the protagonists of Quiet Chaos (Caos calmo, Italy, Antonello Grimaldi, 2008), who are drawn even closer with the young mother’s sudden death on an unconscionably bright and optimistic afternoon, with Dad in a heroic mood having helped rescue a drowning swimmer. Starring and scripted by Nanni Moretti (The Son’s Room, 2001) from the book by prize-winning author Sandro Veronese, Quiet Chaos follows the father, a harried businessman, physically and psychically — although, tellingly, not emotionally — as he goes through the suddenly meaningless machinations of his daily life. That is, until he finds a purpose which gives it meaning: to take his daughter to school each morning and sit outside on a park bench across the street, waiting until the dismissal bell rings.

The cast of characters who pass by his bench and engage him in conversation (or give him suspicious sidelong glances) range from the volatile, expansive, larger-than-life — generally the family members, who richly mine beloved and familiar archetypes of Italian cinema — to the shy and unassuming, who see in him a tolerant and benevolent kindred spirit — to his office-mates and bosses, whose machiavellian chicanery will be familiar to Washingtonians of every professional stripe. But it is his daughter’s unnatural inability to mourn her mother’s death that puzzles and concerns those closest to him, and that will lead him from quiet chaos to life-affirming acceptance. Asked whether he, like his character, would sometimes like to “step out of his life” and be an observer, Moretti said that while there is chaos within him, there is no rest. “I haven’t found the right park bench yet.”

The journey is somewhat reversed in Elegy (Isabel Coixet, USA, 2007), which brings box-office giants Penélope Cruz and Ben Kingsley together in a moving drama based on Philip Roth’s “The Dying Animal” (2001). As it begins, we see college lit professor, author, and self-proclaimed hedonist David Kepesh tell Charlie Rose the story of the maypole, an important part of early American life until the Puritans came in and put an end to the party. We later learn that his own pursuit of hedonism has led him to bed a bevy of female students (after grades have gone in for final exams, of course. The man, after all, has principles).

David is determined to live life according to his own rules, only to find he’s outsmarted himself when he falls head-over-heels for Cuban-born student Consuela, the first bed partner in many a year to really make him feel something. But it scares him; and when she asks him to come to her graduation party and meet her family and friends, he chickens out, calling to say his car broke down. Knowing he’s lying, but not knowing why — her affection for him and generosity of spirit will not allow her to see he’s both terrified of rejection and terrified of commitment — Consuela is devastated, and leaves him. Two years later she calls him with a special request. His joy swiftly turns to anguish, when she gently explains to him what she needs. But he will do it.

At the press conference, director Isabel Coixet confessed to being a huge Philip Roth fan; as with Jeanne Moreau and Later..., Coixet said that when she read “Elegy,” she knew she would make a film of it someday. When she did, it was, as expected, an “intense experience” for her.

Reflecting on his portrayal of David Kepesh, Ben Kingsley said he didn’t want to give him “too many layers,” and as a personal choice, decided to play him in his own British voice — which had made many of us curious, watching the film — despite the fact that the character is American. Kingsley expressed appreciation to Coixet for allowing and encouraging him to feel vulnerability, saying he “felt safe with her” as an actor. Like Coixet, Penélope Cruz also identified herself as a big fan of the book, having read it six years before and calling it “like my bible on the set every day.” Philip Roth never read the script, said Cruz, but had several conversations with her, once telling her: “The body has much more memory than the brain. Always remember that.”

Asked about Kepesh’s statement that you get older in years, but don’t feel any different than you did when you were young — How do you feel about that personally? — Kingsley replied that “it depends on the company you keep. Some people make you feel old, some people make you feel young. Penélope and Isabel kept me young.” And how does Cruz feel about aging? “I’m looking forward to it.” How did she prepare for a role in which she had to play a young woman with breast cancer? Cruz said she understood the character very well, but to understand the sickness, she spoke with women who have been through it: “They never cry when you think they’re going to cry. But when their heel breaks,” they fall apart. Elegy is scheduled for a limited U.S. release this summer.

Keeping roles and personalities separate must have been a challenge second only to that of keeping fact, fiction, and fantasy separate for Guy Maddin, whose “docu-fantasia” My Winnipeg (Canada, 2006), a paean to his beloved hometown, ostensibly deconstructs its history and its residents. Foremost amongst them is his family, led by his formidable mother (played by ‘40s B-movie cult fave Ann Savage). The purported premise for this exercise is his increasing disillusionment with the town he was born in and has never left, and which he fears has bought into the blight of progressivism, “[navigating] itself inexorably away from the enchantment I once knew into the bland oblivion and mediocrity it craves for itself.”

His farewell tour is a considered though regretful repudiation of the philosophy of the great 19th-century railway baron who each year welcomed the first day of winter with a scavenger hunt for young Winnipeggers. First prize? A one-way ticket on the next train out of town. The trick invariably worked: after “a long day spent combing through the city’s nooks and crannies,” Winnipeggers would have a Dorothy moment, and realize that what they’d been searching for was right there all along. But Maddin has decided the magic is no longer there for him, and takes himself, and his perplexed but intrigued audience, on a farewell tour of “this once-beguiling wonderland... through the very birthplaces of my personal mythologies.” We variously meet, or are told of (via Maddin’s wonderfully dry voice-over narration) — (a) the city’s legions of itinerant sleepwalkers (“We show up on old doorsteps... our old homes... and those that live [there] must always take in a lost sleepwalker... it’s the law”); (b) 1930s spiritualist Curious Lou Profetta, famed for “despooking furniture” (plus a streetcar that “was giving passengers the jitters”); (c) the gruesome and perversely but perennially popular horsehead memorial, created eighty years before when horses, fleeing a freak fire during a deadly cold snap, charged panic-stricken into the Red River... only to freeze there, their heads, in eternal expressions of terror and agony, now the site of weekly jaunts by the Holly Snowshoe Club and romantic rambles by strolling couples; (d) and of course, Maddin’s indomitable, no-nonsense, over-the-top mom, who one suspects would be capable of causing similar expressions of terror in more susceptible offspring. “My mom is starting to go blind. Maybe not fast enough for my liking, but she hasn’t seen the movie yet,” Maddin told an interviewer. “She has very strong opinions about how to decode evil sexual thoughts from the most harmless activities.”

Mom’s decoding skills would have a field day, were she to check out Madonna’s directorial debut Filth and Wisdom (Great Britain, 2008), an alternately raunchy and philosophical depiction of the pop icon’s conviction that “It is inevitable that a path paved with filth will often end in wisdom, and one paved with wisdom will often end in filth.” Or, as articulated by the film’s narrator, Ukrainian immigrant, poet and “unparalleled authority on life” (and part-time kinky S&M specialist) AK: If you spend your life doing good, you’ll start searching for filth out of boredom and desperation; if you live your life in filth, you’ll end up searching for beauty. The cast of characters proceed to prove the truth of AK’s somewhat doubtful apothegm. They include a hopeful young ballerina whose search for beauty (her dream to dance with the Royal Ballet) falls flat, so she reluctantly takes a job as a pole dancer in a seedy bar to pay for her lessons; a pharmacy worker who incurs the wrath of her impatient boss by urging customers to put their spare change in collection boxes, and dreams of somehow making a real difference in the lives of starving children in Africa; and a once renowned writer and poet, now blind, for whom AK serves as dogsbody and confidant, and whose existential despair he’s determined to alleviate.

At the press conference — to which your reporter arrived an hour and a half early, only to find the line already snaking down the long Hyatt staircase, through the foyer and out the door — the always outspoken Madonna was the embodiment of her film’s duality. Slinkily yet modestly attired in a long-sleeve, high-neck black sheath, the pop icon was cordial but direct, thanking her questioners for their interest, or scolding and correcting them if their inquiries were somehow found lacking. (“Girl of steel,” ran the headline the following month in Munich’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung, reporting on Madonna’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in New York, and “with an iron smile... Madonna won’t get older, just more sinewy: a girl of steel without an expiration date.”)

“We are all in charge of our lives, and we’re fooling ourselves if we think we’re not,” she told journalists in Berlin, adding that her movie “is about the duality of life and our ongoing struggle with that duality. You can learn and find enlightenment in either place: filth or wisdom.” Did the movie reflect her own life experiences? “I can recall those years of struggle like it was yesterday,” she said, arriving in New York to find that there were “a thousand other girls” who did what she did. “So I had to find other ways of making a living — not pole dancing; I did other things” (sly smile). “I’m still struggling with the duality of life, to see things for what they are, to not be fooled by illusions. I vacillate between light and dark. So I’m not very far away from that.”

Madonna recalled growing up in “a very conventional, narrow-minded environment where people weren’t encouraged to be different,” and identifying with her dance teacher, who was gay. “I always felt like an outsider. He took me to gay clubs where everyone was different, but accepting of everyone’s differences.” The duality of life — light and dark — filth and wisdom — ending, ideally, in acceptance. Which, in the end, may seem a surprisingly idealistic world view for a Material Girl. The session ended with a selection by the film’s star, Eugene Hutz (AK), who took out his banjo and sent us off with a rousing Ukrainian gypsy-punk goodbye.

Idealism plus punk sensibility and a young girl’s dream of ballet also found company a few hundred miles from Kiev, in the multiple-award-winning Rusalka (Mermaid, Anna Melikyan, Russia, 2007), whose director took home the FIPRESCI Prize for Best Director of a film in the Panorama section. Only weeks before, Rusalka had won Melikyan the Directing Award for World Cinema – Dramatic at Sundance, where she was also nominated for the Grand Jury Prize; a year before, its star had captured the Best Actress award closer to home, at the Sochi Open Russian Film Festival.

A whimsical fairy tale with a realist edge, Rusalka is also film that, as a side note, must be filled with insider jokes for Russians. At the press screening, robust laughter greeted lines or shots that left most of us at a loss, despite the subtitles. That being said, there are wonderful bits which, while distinctly Russian, are also universal enough to ring true for anyone. A favorite was what could be called the Russian Harold Hill (from Meredith Willson’s The Music Man, 1962), who appears when there’s an eclipse of the moon. People are cheerfully told to look straight at it because it’s something rare: it means the world is coming to an end. Step right up, pay your money, thank you very much. See you tomorrow!

The story begins at a decrepit resort on the Black Sea, where we meet six-year-old Alisa, nicknamed “Mermaid” by her mother, who dreams of being a ballerina. Her mom, who runs the inn and whose priorities lie elsewhere, will have none of it, and Alisa promptly decides never to utter another word. Her actions, however, speak with far more force: when Mom snags a boyfriend and dotes on him, Alisa sets fire to the house. Now homeless, mother and daughter head for Moscow, where the streets are paved with gold and all things are possible. Well, certainly some things are for Alisa, who develops the power to make things happen just by thinking about them.

What the now-adult Alisa cannot do is keep a job. Depressed after unjustly losing her latest, she jumps off a bridge, only to see a figure plummeting a few yards away. As in a fairy tale, Alisa saves his life, falls in love with him, and he hires her — as his cleaning lady. But the troubles that precipitated his jump have not magically disappeared — as impractical as he is impulsive, his current occupation is selling pre-fab houses on the moon — and he tries a more earthbound solution, running out into oncoming traffic. Our heroine again prevents his imminent demise, this time with her psychic powers. But her job is not yet done: When he books a flight, foreseeing that it will crash with no survivors she convinces him not to fly, fibbing that her grandmother died. The ending comes when we least expect it, and in a way that, true to its Russian roots, refuses to wrap up loose ends.

The loose ends are Korean and Parisian in Night and Day (Bam Gua Nat, Hong Sang-soo, Korea, 2008), as are the film’s roots, which draw from both the Asian emotional palette and the Rohmerian structural template. The film begins slowly: It is late summer. A forty-ish Korean painter has come to Paris to “make a new start”; we later learn he’s on the lam from a marijuana rap. It doesn’t look very promising in Paris, either: His inability to speak French marginalizes his interactions with the locals and thrusts him into the Korean expat community, where he finds a hotel room that “reeks,” which he will be sharing with nine others. But once he emerges into the sunshine, he is in PARIS.

We follow him through a series of chance encounters with ex-girlfriends with whom he once more hooks up, breaks up and/or makes up — sometimes only to start the cycle anew. Unable to find what he’s looking for (or, apparently, to see the incongruity), he calls his wife every day (her night, his day) seeking comfort for his desperate loneliness, as she seeks solace for hers in the sound of his voice. The film is fairly long (145 minutes) and slowly paced, yet the storyline unfolds with such simplicity, nay necessity, that we are never conscious of either its or the characters’ overstaying their welcome. And it is graced with sequences of sheer cinematic poetry that almost defy verbal description: (a) Seong-nam watching a maintenance worker with long, deliberate strokes sweep refuse into the sewer’s swirling waters; we find ourselves counter-intuitively admiring the impressionist stream of leaves, rags, paper, waste, as the strings soar with yearning, reprising the stirring cadences of the second movement from Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony that accompanied the titles. He smiles, perhaps finding the parade of detritus oddly satisfying; (b) a baby bird falls out of a nest at the top of a building where a woman is shooting a film. She picks it up from the sidewalk, concerned but unsure; he tells her to place it on his shoulder. Instead, she gently strokes it, then lifts it up and sets it free; the camera, seemingly on wings, joins it for an instant in flight. We cut to Seong-nam running down the musée’s stone steps, his shirt rippling with the richness of an oil painting, the Beethoven soaring in the background; (c) there is, of course, narrative. Our hero tries to bed all three of his girlfriends before common sense, common decency, modesty or queasiness take over; he gets into a row at another Korean expat’s home where there’s a political discussion and he dares to question the wisdom of the Great Leader. But the storyline is somewhat secondary to the visual and the metaphorical, although the director drew from his own life experiences in developing it.

At the press conference, Hong’s responses were revealing, and occasionally mirrored the one-step-forward, two-steps-backward quality of the film. Acknowledging the influence of Eric Rohmer and others (“I admire many artists, they’re in my heart, I cannot escape from them”), he took pains to emphasize the primacy of both his own vision and his own experiences in creating his films. “Very influenced by daytime/nighttime,” Hong recalled being struck by an incident a few years ago when he was communicating with his wife in Korea, a different time zone from his in Europe, and how whether they were in daytime or nighttime seemed to influence their emotions. This experience may have inspired the film’s title, he said, but cautioned: “My titles do not reflect a deep analysis of the film. It came to me, I liked it, it seemed to fit. A title is made of words. If it sounds good to me, I like it.” Ah, but yet: “There are many, many things I put in the film that connect with the title. It’s up to the viewer to find and appreciate them.”

And what about Seong-nam? Do you like him? Are you like him? “I created him, he represents some parts of me, some of my views. I don’t create a character to deliver a message. Everybody has many sides, so every side must be included in the character.” Hong’s humanist insights would turn philosophical: “Each person has his own reality. We just share some common ground, so we feel we are sharing one reality. For me, dreaming is a part of daily life, so there’s not much difference between dream and waking time, so I can combine them [in a film] with no problems.”

Dreaming and waking... fiction and fact... feature film and docu: The lines continue to soften, expanding and enriching the cinematic template. Opening the fest’s Panorama section — and ending with the section’s Audience Award, beating out 51 other films with a record 20,000 votes — was Lemon Tree (Eran Riklis, Israel/Germany/France, 2008), an affecting, thought-provoking fiction film inspired by actual events. “Based on a thousand stories and one story,” Lemon Tree pits the emotional power and concomitant demands of family legacy against the seemingly immutable ones of state security; in a larger sense, it pits the Palestinian civilian community against the Israeli military. And it does both with remarkable even-handedness.

Because her lemon grove, a potentially optimal hiding place for terrorists, poses a security risk, a Palestinian woman whose home lies across the road from the Israeli defense minister’s is told that the trees must come down. Hiring a young attorney to plead her case (bringing it home to U.S. audiences, Riklis has her call her children in the U.S. to explain the situation: if memory serves, a son who works as a dishwasher at a Dupont Circle restaurant, and a daughter who attends AU), she ultimately finds that she cannot fight the system. While the Palestinian woman, movingly portrayed by Hiam Abbass (for whom Riklis wrote the role; you may remember her award-winning portrayal in The Syrian Bride, 2004) is the character with whom audiences will generally sympathize and identify, Riklis doesn’t demonize her antagonists, but rather gives them Renoirian, “everyone has their reasons” humanity.

“This is a film about loneliness and solitude,” Riklis told us after the press screening. “Everyone is trapped. This is not a political film; it’s a film about people who are trapped in a political situation. To use an American term: It’s a feel-good film without a happy ending... a bit like lemons: bittersweet. I’m a commercial director,” he added, like any good director no doubt contemplating its distribution potential. “I don’t make films for cinémathèques, but for audiences.” How does he think the film will affect the current situation? Riklis refused to speculate: “The burden of representing the Palestinian people is too much for one woman [the film’s lead character],” which goes for the Israeli side as well, he said. “You can’t have a pretentious feeling of changing anything,” added Hiam Abbas. “Just make people think a little bit...?”

That’s something this year’s Berlinale did many times over, sometimes by confounding expectations, displaying surprising or rarely seen sides of known filmmakers and artists, and sometimes by resoundingly confirming them, reminding us of their power to show us new ways of seeing familiar things — or new things entirely. In the latter category must go the opening night film, Martin Scorsese’s Shine a Light (2008), billed as the first documentary to open the Berlinale in its 58-year history, but more aptly described by the director as “not so much a documentary as the capturing of a performance.” The performance? That would be the Rolling Stones’ 2006 concert at the Beacon Theater in New York, where 3,000 screaming fans helped the Stones celebrate Bill Clinton’s 60th birthday. (The film actually captures two concerts, seamlessly spliced together.)

Now, Scorsese + Stones is not a new equation: “This is the only Scorsese film that doesn’t use ‘Gimme Shelter’,” joked Jagger at the press conference to the overflow crowd of appreciative press reps, whose numbers rivaled those of the Madonna contingent. But the onscreen symbiosis of these sixty-ish artists — legendary music makers onstage, esteemed filmmaker backstage frantically managing the mise-en-scène, each palpably, passionately committed to his craft — is a tour de force, shot with powerful immediacy from every angle by seventeen cameras operated by some of cinema’s most distinguished cameramen. And while years of high and hard living may have taken a toll on the rockers’ deeply lined faces, their jaw-dropping stamina and visible, indefatigable, never-say-die exuberance, their sheer joy in doing what they do, leave you both completely drained... and pumped up beyond belief. With all the energy it takes, Dick Cavett asks Mick Jagger in a 1972 interview cut, can you imagine still doing this at 70? “Oh, easily,” he replies. Satisfaction.

Which, true to the dramatic-conflict-ending-in-thought-provoking-irresolution that fest-goers have come to expect and enjoy in their fare, remained elusive in most of the films screened, whether documentary or feature. A notable exception came from a director best known for his work on the other side of the divide, both in genre and in resolution-satisfaction quotient — and whose feature films, as he told the Berlinale in what seems a final, fitting twist, “aspire to the condition of a documentary.”

Happy-Go-Lucky (2008), the latest from the renowned British filmmaker and playwright Mike Leigh (whose Two Thousand Years was opening off-Broadway as his film screened in Berlin), is a 24-hour snapshot into the life of the plucky and delightfully indefatigable Poppy, an almost Candide-like twenty-something whose infectious optimism is both the bane and the boon of those whose lives she touches (including her own) — and whose seeming innocence is both more, and less, than it first appears. She’s someone who can walk into a bookstore and disarm the surly clerk with humor and charm, only to walk out... and find her bike’s been stolen. Whose carefree attitude can drive her pathologically anal, and persistently furious driving instructor around the bend — only to have him, after more histrionics than she (a kindergarten teacher who’s seen it all) can bear, bawl his feelings of inadequacy and failure onto her finally fed-up and unsympathetic shoulder (to scattered applause from the wholly sympathetic — to Poppy — audience. Sally Hawkins was later to win the coveted Silver Bear for Best Actress). Who reserves her gentleness and understanding for the little ones who may not seem to need it (a child who attacks others on the playground), but really do (his home life, as she rightly intuits, is troublesome); for the sister whose love life is less lively than she would wish; for the homeless man in the dead of night who addresses her intensely with streams of gibberish and gobbledygook, which she respectfully answers with interested questions.

Questions aplenty abound (not surprisingly, given its auteur and its placement in the fest’s Forum section, which focuses on experimental cinema) in a film falling squarely on the other side of the complexity-satisfaction equation. Jacques Doillon’s intricate Le premier venu (Just Anybody, France, 2008) serves up three protagonists: a female free spirit who recalls Truffaut’s/Roché’s Catherine, and her two paramours, a policeman and a layabout, who bounce off each other like pinballs that rarely reach a plughole. While that may not bode well for its success on this side of the Atlantic, its elliptical plot and erratic characters are matched by a fluid cinematography and mise-en-scene that should gain it admirers, should it reach our shores.

While the Berlin Philharmonic’s Trip to Asia: The Quest for Harmony (Thomas Grube, Germany, 2008, part of the “Berlinale Special” program) has not yet reached our shores, its Stateside orchestral cousin, the New York Philharmonic, went one measure further two weeks later, reaching those of North Korea for an unprecedented live broadcast, which was reported extensively by The Washington Post, among others. The Berlin orchestra’s 2005 visit, on the other hand, covered China, Japan, and South Korea, and was a long-awaited reprise (and expansion) of their 1979 visit to China, which, conductor Simon Rattle is told, was a great inspiration to Chinese musicians.

The trip was also inspiring and, thanks to the ever-present film crew, even inspiriting for some of the players, whose performances, rehearsals, reactions and emotions, at times surprisingly candid, are captured during the tour. What will strike the non-musician are the behaviors common to members of working groups everywhere. Some players express uncertainty over their own individual prowess, how others in the orchestra look upon them, whether they measure up; others feel frustrated by the lack of challenge the orchestra offers, or by not having the chance to show their stuff and play solo. A striking difference between the orchestra and the office is that for musicians, it doesn’t get any easier with practice or with age, nor do you “automatically know a part after playing it 120 times.” And should you reach that elusive plateau of job-well-done accomplishment, it will not be recognized with plaques, awards or attaboys, and sometimes not even by your loved ones. In one of those moments where you don’t know whether to laugh or cry, a violinist wryly recalls her husband asking her why she works so hard: “Nobody hears you anyway.”

And then of course is their conductor, Simon Rattle, a self-described “person who wakes up every morning with more doubts than the morning before.” But they’re short-lived: “There has to be a metamorphosis. If you haven’t tried to undergo that metamorphosis, then you’d really never better go onstage.” Warming to the subject, he adds: “It’s an unkickable drug habit. And I’m happy to be a junkie to the end of my days.” The reception he and the orchestra receive throughout their trip to Asia, ending with hundreds of thousands of screaming fans in Taiwan, which he rightly describes as “almost orgiastic,” leave Maestro Rattle no hope for rehab.

The same could be said for a man on the other end of the scale in just about every sense, for whom rehab was never an option: the notorious Klaus Kinski, whose ill-fated attempt to bring his version of the Christ story to the stage is chronicled in Jesus Christ Savior (Jesus Christus Erlöser, Germany, Peter Geyer, 2008). The fact that he chose to stage it in a year that had witnessed the federal arrest of thousands protesting a war that was tearing America apart, the recording of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s “Power to the People,” and the opening on Broadway of “Jesus Christ Superstar,” could not have boded well for such a one-man show, whoever presented it. But Kinski?

The audience is obviously out to get him from the start, calling him names and swearing at him as he tries to build his characterization. He promises to portray a different Christ than the one they know, one who despises honors, prayers, and veneration (“I want my 10 Marks back!” someone shouts), invoking the horrors of Vietnam and the screaming mothers who “all call out for Jesus and come to him.” The only calls Kinski hears, however, are the audience’s catcalls. “This group is more fucked up than the Pharisees!” he cries. “At least they let Jesus speak before they nailed him up.” No such luck for Kinski, who will have to wait till the unruly crowd disperses (“Can’t you understand that someone who’s reciting 30 typewritten pages needs some quiet to do it?”) before delivering the speech, without interruption, to a small crowd of devotees. “God,” he implores as Jesus, “at least let them know why I die.”

A cry that also could be uttered by the children conscripted as soldiers in Eritrea, where Jesus is invoked by their teachers — who as nuns either may, or perhaps must, see no irony in their catechism — as prince of peace, in the docudrama Feuerherz (Heart of Fire, 2008). The film, by Luigi Falorni, who may be remembered by DC audiences for The Story of the Weeping Camel (2004), was nominated for the festival’s highest award, the Golden Bear, which may contain an irony of its own: the book upon which the film was based is being threatened with legal action claiming it to be of whole cloth.

The protagonist, a girl of about 10, is taken by her elder sister from the security of a Catholic school to their father, whom she has not seen in years. Her joy is short-lived; she finds her father in a bar, where he is revealed to be a boastful layabout who quickly turns her over to his current lady, who informs her she’ll be sharing a primitive shack (no toilet, no running water) with several other children and expected to earn her keep. Father returns, however, and the child is sure he’s come to take her away from all this.

She’s right; he has. The bad news is, he’s come to sell her to the rebels, who are suffering a shortage of able-bodied men and women, and are now recruiting children. From this point on we follow the child’s life as a soldier in the Eritrean Liberation Front. It’s told with compassion and clarity, but tending toward the PG, as we watch relationships and personalities develop through sharing and loss, with a minimum of blood and a maximum of “growth.” The controversy that has arisen around the film could, as always, be either bane or boon; no U.S. release dates as of this writing.

Addressing the brouhaha at the press conference, the film’s producer emphasized that it is a fictional film based on extensive research, and agreed that the children who served were never forced to take part in hostilities (a point made by the protesters), but volunteered. The moderator suggested that the film be seen more generically, as a parable of military service by children, wherever and whenever it has occurred. Falorni differed, saying he didn’t want to make a film about child soldiers, but about one girl and her experience, and to leave one with hope at the end.

Hope springs eternal for the seventy- and eighty-plus-year-old tango musicians whose preparations for a farewell concert take center stage in Miguel Koban’s Café de los Maestros (Argentina-USA-Brazil, 2008). It is, in a sense, a sort of Shine a Light of the tango; as with the Stones, their energy, their undimmed passion for what they do, are boundless and ageless. But here, it is the music that is the undisputed star. A rousing, warmhearted look at the musicians and their love for each other, their instruments, their music and their country, the film was inspired by a double CD showcasing the musicians that was put together in 2005 by composer Gustavo Santaolalla of Brokeback Mountain fame.

Everyone sings or plays in Argentina, we are told, and cafés once were king. “If a guy went to a concert, it was to pick up a chick. But if he went to a café, it was to listen.” And once the passion seizes you, it doesn’t let go. “When I go,” says a bandoneon player, patting his stringed, box-like instrument, “I’m taking it with me.” The only woman in the group, Virginia Luque, a popular actress in her youth, has very definite ideas about interpretation. “You have to dress each song differently, so it fits into its clothing,” she says, adding: “You can grow tango anywhere, but it only grows roots here.”

The roots grow surprisingly deep and the outfits shift with alarmingly speed in Heaven’s Heart (Simon Staho, Sweden-Denmark, 2008), another film selected for the “Berlinale Special” program. Unlike Café, it begins with all the excitement of a funeral; which, in a way, it is. We are in a judge’s chambers. Lars and Susanna, a middle-aged couple, sit, expressionless, as the assets are divided up: the final step in their divorce.

Flashback to happier days, just nine months earlier, when their best friends come to dinner. The friendly and intimate conversation turns to the adulterous affair of one of Lars’ colleagues. Both couples respond as expected of 20-year happily-marrrieds, saying they never could imagine doing something like that to their spouses, the men allowing that they could understand it happening to someone not as content as they, the women teasingly telling them what they could expect, should they ever act on their “understanding”. The women now in the kitchen, Ulf, with a surreptitious glance at Susanna, admits he might not have married had he known Ann couldn’t have children. That night, Susanna tells Lars she dreamed of making love to an old boyfriend the night before. And the impossible but inescapable descent begins.

In the Q&A, director Staho said he’d wanted to make a movie that would show the brutality of living together. Adultery is usually shown superficially in films; he wanted to show “what it’s like when you’re punched in the face by someone you love.” To the inescapable question: Was he inspired by Bergman’s classic Scenes from a Marriage? Staho, a youthful 36 whose films have won awards at Chicago and San Sebastian, replied firmly: “That was from a different era. You can’t be influenced by something that’s dead. There was no influence by that film.” Well, certainly not in terms of runtime. Whereas the Bergman runs either 167 minutes (theatrical release) or 299 minutes (TV version), Staho’s clocks in at a concise 95. But then, Staho is in thrall to the editing process, “throwing out the best bits, cutting it down to the bone as far as possible. It’s a duty,” he told us earnestly, “to do that.”

Conversations/confrontations of an utterly different sort between two middle-aged couples are also key to Zuo You (In Love We Trust, Wang Xioashuai, People’s Republic of China, 2008), which won the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay and was nominated for the Golden Bear for Best Film. But that is where the similarity ends; the challenges these couples face could not be more disparate. The adored daughter of a loving couple is diagnosed with leukemia. After chemo treatments fail, her devastated parents are told that her only hope lies in a bone marrow transplant from a compatible donor. The best match would be a brother or sister, but she is an only child, and will survive for at most two to three years without a transplant. Complicating matters is the fact that she is the offspring of the woman’s first marriage. Will her ex-husband agree, his current marriage already on thin ice, to give her a child? And will the child’s step-father agree to his wife’s bedding her ex-husband for the sake of their daughter?

The answers to those questions play out incrementally in narrative shot-countershot, as each of the couples discusses the situation, then proceeds to act on the decision or understanding reached. There are flashes of humor, as when the ex-husband goes to the lab and is asked to give a sperm sample, is given a tiny cup and directed to a small bathroom with X-rated magazines, ostensibly to speed the process. And too there is visual beauty, most strikingly as the couple make loveless love in a room with sheets of undulating blood-red satin, a wordless ballet of bodies filmed from the waist down, the sheets rippling with their desperate, joyless movements. The joy will come later...

At the press conference, director Wang, asked to comment on the increasing westernization of China reflected in the film, replied that in China, everything is very fast moving, with tradition “only to be found in history books.” The capital city “has become very international, very modern. This film could take place anywhere.” As to the subject matter, while the need for bone marrow transplants and the attendant requests for donors have been the subject of recent media attention in China, it’s the story of the adults that interested him. “I hope that when confronted with such a disaster, people will use love and rationality to deal with it. My hope was to have love reign in the relationships. The essence is how middle-aged people deal with catastrophe in their lives. That’s what I wanted to show.”

How middle-aged people not just deal with but also cause catastrophe is shown to less persuasive effect in Fireflies in the Garden (Dennis Lee, USA, 2008), an all-star vehicle that generally imploded with critics (“Garden sprouts weeds” ran Variety’s head), but was distinguished by and widely credited with fine performances and some genuinely moving sequences. The storyline, however, too often seems less a line than a narrative string game whose characters weave in and out of eras. Ageing without explanation or warning (but aided by desaturated stock, muted colors and hand-held camera in certain sequences), they try, now as children, now as adults, to deal with the deep psychological scars left by a frighteningly demanding and punitive father and the death in an automobile accident of a spirited, but for all the good it does anyone, essentially powerless mother (played by Julia Roberts). Threading through the film’s twenty-two years is the threat of the lead character, whose childhood torment we witness, to get even with his father by baring a few well-kept secrets in a semi-fictional tell-all book.

Willem Dafoe answers questions at the Berlinale

In the Q&A, lead actor Ryan Reynolds diplomatically addressed the confusion question — “What’s significant in these relationships is not what’s said, but what’s unsaid” — followed by director Dennis Lee, who told us, “We leave it to the audience to create the backstory.” Willem Dafoe, who plays the empathy-challenged paterfamilias, called him a loving but brutal father who has to deal with the loss of his wife. Does he himself resemble the the father? “In a way, I recognize myself in him. My father subscribed to such a model for happiness... inflict incredible cruelties in the name of love.” Lee’s sister saw the film; his father, whom he told the script was a compilation of his life and those of several friends, was fine with it. “I feel blessed” to have had his family, said Lee, who was lauded by his cast for creating a harmonious one on the set. “You’d never guess it was his first film,” said one of the actors. “He established an incredibly collaborative environment.” Lee’s mother died in an accident while he was in film school; he made Fireflies, he told us, in honor of both of his parents.

“The suffering of children throughout the world runs like a red thread through the films of the 58th Berlinale,” observed the German journal n-tv. If in Fireflies, the child’s pain is like a knot that tightens, in Julia (Erick Zonca, France, 2008), his suffering is secondary to the twists of the drama. The formidable Tilda Swinton has a field day as a frowsy alcoholic who wants to make something of her life but refuses, or is unable, to control the one thing that stands in the way: her drinking. Bailing out of an AA meeting after listening from the door for 10 seconds, she finds herself drawn into the scheme of a young woman who saw her there, and sees in Julia her salvation: a woman with the guts (and desperation) to help her kidnap her son from his mega-wealthy grandfather. And what’s in it for Julia? $50,000.

When she finds out the woman doesn’t have the money yet, Julia raises the stakes considerably, and decides to do it herself — for millions of dollars in ransom. And thus begins the kidnap caper, which takes her across the Mexican border and through every cinematic kidnap cliché in the book, intermittently spiced with violence, wit, and surprising warmth.

At the press conference, Swinton was greeted with cheers and resounding applause. Asked whether he had been scared of Swinton — hysterical and, in her kidnapper role, fiercely intimidating — the appealingly self-assured Aidan Gould, who plays the boy, responded that “she is so compassionate, she’d try to calm me down, but I wasn’t scared of her, because — it’s a movie!” Chimed in Swinton, “It’s just dress up and play, not any deep psychological exercise... I spend my life playing with people of Aidan’s age, so it was very natural for me.” How did she prepare for the role? “I’ve spent my life being around alcoholics and always being the sober one. Hanging around drunks is all the preparation you need.” Added director Erick Zonca: “Unlike Tilda, I like to drink. There are two sides of it: the happy, pleasure part and the mean, manipulative part, where you trick people to get what you want,” as portrayed so dynamically by Swinton, who was short-listed for the Best Actress Golden Bear.

Zonca said it took him three years to write the story, and that while he adores John Cassavetes’ films and acknowledged his influence, it is, Swinton interjected, “not a remake of Cassavetes’ Gloria or Opening Night”. Unable to obtain financing in the U.S., the film was produced by Studio Canal in France. “We are all juggling, negotiating different parts of ourselves, doing one thing while being half-focused on another,” said Swinton. “Erick is a doctor of zoology, amoral and compassionate, truly modern... It’s what I’ve been waiting for.” Swinton spoke warmly of her mentor Derek Jarman, “my filmmaking root... It’s a crime that he’s so little known,” and urged us all to see the documentary Derek screening in the Panorama section. Swinton would receive an honorary Teddy 22 Queer Film Award honoring her work with Jarman, with whom she made seven films.

Queer indeed, and intriguingly so, was Teddy entry Drifting Flowers (Piao Lang Qing Chun, Zero Chou, Taiwan, 2007), the third movie in Zero Chou’s ongoing “Rainbow Colors” project. The film was preceded by the short, No Bikini (Claudia Morgado Escanilla, Canada, 2007), in which a seven-year-old is given her first two-piece bathing suit along with a warning from her mom that “you’re gonna have to watch out about that” when she raises her arms and the top rides up all the way, finding no resistance. Fed up with the constriction, once at swimming camp she finds a practical solution that shocks her mother, but would certainly find resonance with the adult protagonists of the feature that followed: she takes off the top, and with great relief, passes for a boy.

Drifting Flowers’s Diego deals with the bra question on another, deeper level as a teenage girl who refuses to wear the frilly one her mother buys for her, instead binding her breasts so as to look more like the boy she feels that she is and so wants to be. We first meet her as the lover of the beautiful Jing, a blind nightclub singer whose little sister idolizes Diego. Social services get wind of the child’s unorthodox living arrangements — nights spent at her sister’s smoke-, drug-, and noise-filled place of employment — and convince Jing to place her in foster care, where she flourishes. But Jing can’t bear the separation, and takes the child back, only to have her awaken in the middle of the night to see Jing and Diego in a passionate embrace. Her reaction is indecipherable — shock? confusion? revulsion? Or something else entirely? The foster mom soon gets wind of it, and gently asks Jing if it might not be best for the child to break off all contact with her. Fast forward 10 years: The girl comes home from college, mom is there waiting for her, and the girl and Diego spontaneously engage in a big, mouth-to-mouth kiss. Nurture, or nature...?

A question that takes us in a whole ‘nother direction in the Spanish-titled Italian film Corazones de mujer (Woman’s Hearts, David Sordella, Pablo Benedetti, known collectively as “Kiff Kosoof,” 2008), a Moroccan road movie about a young woman in search of something that those of us living less sophisticated lives, always assumed was more or less irretrievable: her virginity. Her impending marriage into an Arab family will be completely upended, as will she, if they find out she’s not a virgin.

Enter Shakira, a Moroccan transvestite dressmaker who knows of a place in Casablanca where they specialize in operations to restore what has been “lost.” And we’re off to the races: a madcap combination of languages and cultures, color and black-and-white, hand-held, crane and dolly, genres, shooting styles and music styles, with ancient and modern blending incongruously but inescapably (they travel in an ancient Alfa Romeo that breaks down in the middle of the desert. “What are we going to do?” she asks him. “Call Desert Help Assistance” he laughs) ensues. Woman’s Hearts is, we were assured, based on a true story told to the directors by “a transvestite tailor in a smoky bar.” The frequent, lighthearted repartee does not disguise the underlying tensions: the woman confessing her fears that marriage will bring her the same violent abuse her mother endured and unsuccessfully tried to hide; the mocking jeers and vicious assaults directed at gays, cross-dressers and transvestites; the heartbreak that ensues when one fathers a son, loves him, but cannot tell him, or fears to tell him, that he is his father.

“This is a film without borders,” said the directors after the screening. In the real world, of course, there are borders; and there is one that the directors particularly hope to cross with their film: that of the Arab world. If all goes as planned, it will happen in December, at the Dubai International Film Festival.

The borders harried Japanese businesswoman Taeko must cross in search of the ultimate chill-out are both behavioral and geographical in Noako Ogigami’s Megane (Glasses, Japan, 2007), which, as it happens, won the festival’s Manfred Salzgeber Prize for “a film that broadens the boundaries of cinema today.” Arriving at her hotel after a long hike down a deserted beach, the handle of her heavy metal suitcase in one hand and a minimally helpful map in the other, she finds the place apparently unoccupied. At last a man emerges, congratulating her on her sense of direction: she’s the first person in three years who didn’t get completely lost. Famished after her long trip and fatiguing walk, she asks for the menu, only to be cheerily told to help herself to whatever’s in the fridge. She opens it to find little but a huge fish, balefully staring her in the face. Fortunately, it will soon become the centerpiece of a feast of delicacies, their preparation and provenance explained to the assembled guests in excruciating (or fascinating, take your pick) detail.

Our businesswoman soon finds this rather eccentric hotel to be equipped, fittingly, with a routine not found in even the most intimate B&Bs: each morning, she awakens to a cheery “good morning” from an old woman who kneels patiently beside her bed, waiting for her to come to and follow the surely irresistible sounds of the player piano, whose waltz-like tunes waft in on the gentle breeze. At last she does, and finds a group of children on the beach doing tai-chi-like “merci exercises” in time to the music. Oddly charming though these may be, the charms of the island itself soon begin to wear thin. What Taeko wants is a guided tour. Her hosts and fellow guests look at each other in puzzlement. What could she possibly want to see? People generally come here to eat Sakura’s exceptional shaved ice and to engage in “twilighting,” i.e. lying back and reflecting on their past, or upon someone special in their lives.

Well, that’s about all the excitement she can take. She will leave, but soon return, finding, as Guy Maddin’s Winnipeggers, there’s no place like home (or in this case, hotel). “Why did you come [originally]?” she is asked. Her reply brought knowing chuckles from the audience: “I wanted to come to a place where there was no cell phone reception!”

At the Q&A following the screening, Ogigami was asked about the title: Why “Glasses”? As whimsical as her film, the director replied disingenuously that maybe it was because whenever she and her colleagues have a meeting, “we always wear glasses.” And, too, everyone in the film wears glasses. (Those of us who have yet to go Lasik felt validated.) Praised for the film’s mellowness, Ogigami, who studied film in the States, recalled her professor’s telling her that “a film always has to have a conflict. I said, why?”

One reason may be because those are often the films that have it both ways, winning big at the box office while reaping the top fest prizes. A case in point: this year’s Golden Bear winner, Tropa de Elite (The Elite Squad, José Padilha, Brazil, 2007), which also was the largest-grossing film last year in its native land. Interestingly, in this case the conflict was both diegetic and extrinsic. The film’s unapologetically blood-soaked depiction of thug and drug violence in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, and of the equally bloody brutality of the “elite squad” of police officers who deal with it (BOPE), have given rise to spirited debates in Brazil over both the subject matter and its portrayal.

At the heart of this dispute lie two diametrically opposed ways of looking at and dealing with an evil whose malignity no one (except perhaps its perpetrators) disputes. While the methods used by the BOPE as portrayed in the film would make Dirty Harry feel right at home, can their intended ends, plus the repellent nature of the crime they are trying to eradicate, justify the use of equally repellent means to fight it? The film also pushes sensitive buttons on highly charged social issues, including the effectiveness, as well as the motivation, of those who try to assist slum residents; the drug habits of the wealthy, which help keep the dealers in business; and the failure of both government and societal mechanisms to improve the lot of Rio’s poorest and most desperate.

In an interview with the newspaper Die Welt, director José Padilha defended his film, asserting that everything in it really happened, the characters are based on real people; the research took two years, and the screenplay was vetted by a former member of BOPE. “The reality,” he added grimly, “is probably much worse.” Padilha’s own views on drug crime and its causes would no doubt be viewed with equal disfavor by those he implicitly criticizes in his film. “If drugs were legal, like cocaine used to be in Brazil — you could buy it at the drug store — there wouldn’t be this crime and violence. It’s like in the USA, when alcohol was forbidden there was a higher murder rate. In Holland [where drug use is controlled, not criminalized], you don’t hear anything about corrupt policemen who torture and kill.” Are you seriously arguing for the legalization of hard drugs? “Over half of all drug profits come from marijuana, which in my opinion should be decontrolled. I think alcohol is way more dangerous. And yes, I’m for the controlled distribution of drugs. If somebody in New York or Berlin or wherever wants cocaine, he finds a way to get it. That’s a fact. It’s just a matter of how he gets it” [my translation — L.W.].

Frank talk from a filmmaker who doesn’t pull punches, either in his films or in his words — and an unusually controversial choice for the Berlinale’s highest honor. But that should have come as no surprise to anyone, given the makeup of the jury, headed by the renowned director Costa-Gavras, who has never shied away from controversy and whose oeuvre includes the political thriller and Oscar winner Z (1969) and the Chile-putsch powerhouse Missing (1981). Significantly, the jury also included multiple-Oscar-winner Walter Murch, acclaimed for his work on Francis Coppola’s cinematic cause célèbre Apocalypse Now (1979), and production designer Uli Hanisch, honored with three German film awards for his work in Tom Tykwer’s terrifying and macabre Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006). Actress and producer Diane Kruger, Russian producer Alexander Rodnyansky, and Asian actress Shu Qi completed the jury.

In an interview with Christiane Peitz for the newspaper Tagesspiel [my translations – L.W.] the Greek-born Costa-Gavras, who, coincidentally, celebrated his 75th birthday during the festival, recalled his first visit to France in the 1950s, when he “learned something important: that a person is responsible for the society in which he lives.” Costa-Gavras spoke emotionally about the difficulties faced by African immigrants in Europe, which inspired him to write a screenplay for new film, East is West, hoping to work on it in his free moments during the festival. The situation he speaks of is not unique to Europe; his anger and frustration find purchase with immigrant advocates in developed countries everywhere.

“The refugees have no more dreams where they live,” he said. “Their dream is Europe, and we take even that dream from them. It makes me angry, that we degrade and humiliate them and send them home to their families with empty hands. We throw them away like second-class people.” Why has the situation for immigrants changed so drastically since the ’50s? “Those were different times. The industrialized nations desperately needed workers then; today, we continue to treat even the children and grandchildren of immigrants like foreigners.” Can cinema do something to help this situation? “Yes. It can show what happens when there’s no respect.” Then you want us to feel ashamed? “Shame is good. Why are films here? They help us develop feelings. The viewer should feel ashamed or sad or happy. That’s important, because all of our actions are based on feelings.” You once said hate is a good motivator, he was reminded. “When I made Z, I was filled with hate against the Obrist regime. Why do you hate something? Because it threatens what you love. Hate is a good feeling. Of course you have to control it and change it into something creative.”

Which Costa-Gavras has undeniably done for half a century. But— what about the age-old argument between art and commerce, we might ask, class vs. mass? You seem to have been able to have it both ways, Mr. Costa-Gavras, a singular accomplishment that few filmmakers achieve. Or — to put it as the Tagesspiegel interviewer actually did: Why do you always build mainstream elements into your films? “Because I’m putting on a spectacle, a show. The Greek theater, Molière, Shakespeare, Brecht — all spectacle. Whoever goes to the movies isn’t going to a political meeting. I just showed my grandchildren Modern Times, and I noticed again how unbelievably current Charlie Chaplin is. Now is that entertainment, or art-for-art’s-sake? It’s neither one. Movies are art for a large audience.”

A better definition — and a better wrap for this year’s Berlinale — you couldn’t find. See you next year!

NOTE: Photos courtesy of the Berlinale Website.