The Magnificent Welles: Rarities in Switzerland

By Leslie Weisman, DC Film Society Member

Locarno! The name was not at all familiar when a colleague told me unequivocally that for a dedicated "Wellesian" like me, the upcoming Locarno International Film Festival, which would be pulling out all the stops in celebration of Orson Welles' 90th birthday, was not to be missed.

Locarno is a picture-postcard city on the shores of Lake Maggiore in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, located in the southern canton of Ticino, about 275 miles from Geneva. This international film festival, now in its 30th year, was host to 189,000 visitors. Switzerland's multi-lingual populace is at home in German, French and Italian, with English in most cases, a distant fourth. So--in an eye-opening and instructive experience for the chauvinistic Yank--while Americans will find themselves warmly welcomed, it usually won't be in English. Exceptions to the rule are found mainly in business and advertising; the daily festival paper Pardo News, in a casual display of linguistic virtuosity, placed reports in the four languages right next to each other. That said, since film is an international lingua franca, American cinephiles could easily feel at home at the Locarno International Film Festival, where honorees this year included Susan Sarandon, Terry Gilliam and John Malkovich, and the closing-night film was Robert Altman's Nashville. For details on the festival, visit the website.

Locarno is a picture-postcard city on the shores of Lake Maggiore in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, located in the southern canton of Ticino, about 275 miles from Geneva. This international film festival, now in its 30th year, was host to 189,000 visitors. Switzerland's multi-lingual populace is at home in German, French and Italian, with English in most cases, a distant fourth. So--in an eye-opening and instructive experience for the chauvinistic Yank--while Americans will find themselves warmly welcomed, it usually won't be in English. Exceptions to the rule are found mainly in business and advertising; the daily festival paper Pardo News, in a casual display of linguistic virtuosity, placed reports in the four languages right next to each other. That said, since film is an international lingua franca, American cinephiles could easily feel at home at the Locarno International Film Festival, where honorees this year included Susan Sarandon, Terry Gilliam and John Malkovich, and the closing-night film was Robert Altman's Nashville. For details on the festival, visit the website.

For the dedicated Wellesian, Locarno was true nirvana. From 9:00am to 1:00am--16 hours a day, for eleven days and nights--the EX*REX and La Sala theaters were nothing short of paradise for those who wanted to feast on the master's films and filmic essays, starring roles and character studies, Shakespearean incarnations and (yes) beer and wine commercials--many of them rarely if ever seen publicly since they were first shown.

The screenings were accompanied by first-hand reports (workshops) from those who worked with Welles, lived with him, learned from him, made films about him--or studied him, becoming known and respected in their own right for their expertise on the man and his work. There were warm and informative reminiscences on stage from those who loved him, including Welles' daughter, Chris Welles Feder (see photo at right)--and the occasional shiv on screen, from those who (in the memorable words of Mr. Rawlston in Welles' magnum opus, Citizen Kane) hated his guts. It was, in short, a prismatic view of a great man through the eyes of those who knew him. Whether in the end he would have been pleased or dismayed, no one can say. But he certainly would have appreciated the irony. And those of us lucky enough to be there came away knowing more--and, true to the paradox, being sure of less--than ever before.

The screenings were accompanied by first-hand reports (workshops) from those who worked with Welles, lived with him, learned from him, made films about him--or studied him, becoming known and respected in their own right for their expertise on the man and his work. There were warm and informative reminiscences on stage from those who loved him, including Welles' daughter, Chris Welles Feder (see photo at right)--and the occasional shiv on screen, from those who (in the memorable words of Mr. Rawlston in Welles' magnum opus, Citizen Kane) hated his guts. It was, in short, a prismatic view of a great man through the eyes of those who knew him. Whether in the end he would have been pleased or dismayed, no one can say. But he certainly would have appreciated the irony. And those of us lucky enough to be there came away knowing more--and, true to the paradox, being sure of less--than ever before.

The Program

A pleasant surprise for English speakers was that the Welles retrospective was conducted almost entirely in English, with headphones for those who needed translation. The guiding principle seemed to be that, as Welles was an American filmmaker, the dominant language should be English, which appeared acceptable to everyone. Films produced in other languages generally had English subtitles, while British productions, if made for the European market, usually had titles in French and/or German. It may well be impossible to do full justice here to the scope and richness of the program, which in addition to the workshops, screened approximately 75 films by, with, and about Orson Welles. The retrospective was curated by the Munich Film Museum, which organized two similarly ambitious Welles conferences in Germany (Munich in 1999, Mannheim in 2002), as part of the Film Museum's triennial Welles retrospective.

To begin, a trailer:

From rarities such as Welles' filmic essays on Spain and Italy, to the pot-boilers he made there to finance his own films...

...from the legendary, unfinished The Other Side of the Wind, and the equally legendary "When-Are-You-Going-to-Finish-Don-Quixote," to tales of the byzantine intrigues that, decades later, continue to keep them unfinished...

...from the ill-starred The Magnificent Ambersons and It's All True, to the conspiracy theories about them that have become part of their legend...

...from enlightening analyses and informed reconstructions of Confidential Report (also known as Mr. Arkadin), to regretful acknowledgments that its labyrinths may never be penetrated, nor its knotty plot untangled....

...from the recently restored footage of his hauntingly beautiful The Dreamers, to the haunting realization that this was perhaps his most personal, and final, film...

...from the gift for impersonation so visible in his performances, to the passion for magic that invisibly informed his directing...

All this and more: an unprecedented dozen days, exploring that self-proclaimed one-man band, that universally acknowledged, widely admired and acclaimed, multiply talented maverick: The Magnificent Orson Welles.

Films with Welles

Films featuring Welles as actor were reliably, and sometimes even surprisingly popular with fest-goers. Jane Eyre received some of the warmest applause of any film, as did Black Magic, which even garnered approving cheers from some quarters. In addition to the familiar, there was also the relatively rare (not always, as Welles himself would be the first to say, unjustly so): the Belgian Malpertuis, the British Lord Mountdrago and I'll Never Forget What's 'is Name, the British/French The Southern Star, the Italian 12+1, the Italian/Spanish Tepepa, the Italian/French La Ricotta and La Decade prodigieuse, and the Italian/American David and Goliath. The dual production parentage of many of these films recalls Welles' own wanderings and the warm welcome he received abroad, where his genius was often more readily recognized and appreciated than in his homeland.

Films about Welles

One of the most rewarding aspects of the retrospective was the opportunity it offered participants to see, within the space of two short weeks, seventeen films on Welles by filmmakers who had known him, worked with him, or been inspired by him. From the worshipful to the damning, from the objective to the objectionable, the films provided a revealing look at the impact Welles had and continues to have on his peers, and (as the notorious Louella Parsons might have said) would-be peers.

The Big O (France, 1989) by Andre Sylvain Labarthe, is framed as a detective story, with writer-actor Howard Rodman on the path of Welles' own "Rosebud," interviewing Welles experts and associates in a search for clues. John Houseman (in what may have been his last interview), clearly not having mellowed with time, calls Welles a megalomaniac, and insists that Welles did not write "Kane," nor did he "do everything," as he allegedly claimed. Offering what he may have thought was a palliative, he adds: "But he really thought he had." The director's heavily accented English (he narrates the film) is somewhat problematic, and ruefully recalled for this viewer Italian claims that Welles' Italian wasn't good enough for him to be allowed to narrate the shows he made there (though others--including if memory serves, Ciro Giorgini, researcher/programmer for Italian television--said Welles had excellent command of the language, and spoke it with hardly any accent).

The Other Side of Welles (Croatia, 2005) by Daniel Rafaelic and Leon Rizmaul, had its English-language premiere at the festival; even Welles' incomparable voice was dubbed in previous screenings. Beginning as a docudrama, with actors playing Welles and his family in a reconstruction of key points in his life, it soon breaks off, and we see Welles himself sitting relaxed on the set of a TV interview show, where he responds openly to questions about his work in, and love for the former Yugoslavia. The film serves as an affectionate look back at his work there, where the money he earned by acting (David and Goliath) was immediately put into his own films (e.g. The Deep), which he shot in its crystal-blue waters when he was off the set.

RKO 281 (Great Britain, 1999), Benjamin Ross' docudrama follow-up to The Battle Over Citizen Kane, sees it as a decisive conflict between two giants--one emboldened by youth, and almost limitless talent, the other by power, and almost limitless wealth. Some fine performances, including John Malkovich as Herman Mankiewicz and Melanie Griffith as Marion Davies. You may have caught this one when it premiered on TV.

Shadowing the Third Man (Great Britain/Austria/France, 2005) by Frederic Baker was an informative and cinematographically inventive look at the making of The Third Man. Using a new technique called "Projectionism," the film superimposes scenes from the 1949 film onto interviews with those who worked on it and present-day shots of the original locations.

Orson Welles (France, 1968) is a curious compilation of clips, narrated by Maurice Bessy, of Mr. Arkadin (the novel) fame. Some of the clips are rare (Orson the salad chef tossing greens and vinaigrette as he jovially confides the ingredients of his special recipe; Orson the animal lover, nuzzling a large and appropriately vocal parrot on his shoulder), and are intercut with shots from an interview with Jeanne Moreau ("You're always alone, Orson said. It's the human condition").

O signo do caos (Brazil, 2003) by Rogerio Sganzerla is a disjointed but entertaining collage mixing broad comedy with "Pink Panther"-like whodunit, hypothesizing that Brazilians conspired to steal and destroy It's All True because it made the country look bad. The thieves seem ecstatic to be ridding the world of the film, with one calling it "a threat to our policy of good neighborship," a play on the "good neighbor policy" Welles was supposed to be promoting with it.

The Night That Panicked America (U.S., 1975), Joseph Sargent's dramatic semi-fictional look at the impact of Welles' notorious "War of the Worlds" broadcast, was extremely well received, while Jay Bushman's short Orson Welles Sells His Soul to the Devil (U.S., 1999), a razor-sharp, speculative leap into 1937 New York and Welles' staging of Doctor Faustus, gave viewers much to chew on, which doubtless remained with them longer after the film's swift "light's-out" close.

Attendees also had a sneak preview, in the form of a promo reel, of Citizen of America, a film-in-process by Welles scholar and filmmaker Robert Fischer and fellow Welles scholar Richard France. The film tells the little-known story of Welles' determined efforts in behalf of Isaac Woodard, a black World War II veteran viciously blinded by a sheriff in 1946 South Carolina. (One suspects that Welles--who told Leslie Megahey in The Orson Welles Story his greatest regret was that he'd spent far more time trying to find money to make his pictures than making them, and students at the Cinémathèque Française that "The greatest moment of your life is when you know the money's in the bank"--would both commend this project, and not incidentally, empathize with the need to find funding to finish it.)

A number of films and TV shows attested to Welles' great love for Spain and the Spanish people, as well as to his lifelong passion for la corrida (in the film Brunnen, described below, Welles is quoted as saying: "A bullfighter is an actor to whom real things happen"). Among them were Carlos Rodriguez' 2000 film Orson Welles en el pais de Don Quijote, Welles' own film made in 1955 under British auspices, Madrid: The Bullfight, and a series of nine films made for Italian television, but never seen there. Two Welles associates, Ciro Giorgini and editor Roberto Perpignani, restored the series "the way he would have wanted it," though Giorgini disclaimed the word "restoration" ("it's like a slide under a microscope"), emphasizing the vitality of the films. Film Museum director Stefan Droessler called the series a major work and a new form created for television. The films, which are like elegant home movies with a Wellesian perspective, employ Welles' signature wide-angle, low-angle, and fish-eye shots. Taking the viewer on tours of Italian shops and museums and the Spanish countryside with his wife and small daughter in a horse-drawn carriage, Welles chats with shopkeepers and villagers, filming the famous windmills from a striking low angle, illustrating Don Quixote's famed claim that they must be giants.

Brunnen (Fountain, Sweden, 2005) is director Kristian Petri's first-person account of his travels to places Welles lived in, worked in and frequented in Spain. Inspired by Welles' richly evocative portraits of Spain and its history, culture, customs, and people, Petri came to see if any traces of Welles remained there, fifty years after the first was made in 1955. After the distressing discovery that the new owner of Welles' villa had promptly burned all the books in the great man's library, Petri is heartened to find a plaque in the village square honoring "San Orson Welles." His relief is short-lived: visiting Jess Franco, who infamously (in the eyes of most Wellesians and film scholars) "finished" Welles' Don Quixote, Petri is told that Welles was mercurial and compulsive, re-viewing his films "100 times" and continually finding new things to fix, habitually fueling his obsession with "enough food for three people." Franco also allows that Welles had a prodigious appetite for filming, with a propensity for driving around the city with a 16mm camera on the principle that "You never know what's around the corner." As to the widely accepted story that Welles asked to be cremated, his ashes interred in a well at the home of his friend, the celebrated matador Antonio Ordonez, in San Cayetano, where they now rest--a claim also asserted here by Jess Franco--Petri learns that there is an important witness who uncompromisingly disputes it. Speaking with Oja Kodar, Welles' closest associate during the last two decades of his life, Petri finds that not only did Welles not wish to be cremated ("I took so much from this earth," he told Kodar, "I want to give something back"); he wanted to be buried in the little hamlet in rural Spain where he filmed Chimes. But she had no say in the decision, which was made by his family. The film also includes interviews with local people from all walks of life, who say Welles was unpretentious and treated them with warmth, humanity, and respect.

Welles' love for Italy also received its due, if not always returned in the films. Rosabella (Italian for "Rosebud") (Italy, 1993), by Gianfranco Giagni and Ciro Giorgini, recounts Welles' life in Italy during his marriage to the Contessa di Girfalco, Paola Mori. Filled with affectionate, humorous reminiscences on the one hand, and acrimonious, judgmental recollections on the other--sometimes from the same people--this is a bipolar, but nonetheless instructive, film. (A new DVD of the film with "lots of extras" is planned to be released in conjunction with the 20th anniversary of Welles' death in October.)

Orson Welles Uncut (Belgium, 2005) by Francoise Levie, really had the knives out. Pursuing the shooting of the 1971 Malpertuis (which had an 11:30 p.m. screening at a somewhat remote location--your otherwise indefatigable reported bagged it), it gives vent to co-workers' seemingly nagging, niggling complaints about Welles' alleged abusiveness, backwardness, and just plain dysfunctional-ness. In a post-screening discussion, the director defended herself against suggestions and accusations of an anti-Welles agenda, asserting that she simply recorded what Welles' disaffected associates told her, and that the shots of Welles being difficult on the set were legitimately recorded, and not off-camera shots. Droessler reminded the audience that Welles' impatience with the crew's perceived incompetence may have been due, at least in part, to the fact that he was playing this unprepossessing role to earn badly needed money for his own films. Malpertuis was just released as a double DVD, with the director's cut that screened at the festival.

The Magnificent Welles (U.S., 2002) is the superb one-man show by Marcus Wolland for Stage Direct in Seattle, depicting the consummately type-A Welles on the phone from Rio trying desperately to sort out the twin-debacles-in-the-making of The Magnificent Ambersons and It's All True. Available on video, it's a worthwhile addition to anyone's "about Welles" library.

The Orson Welles Story (Great Britain, 1982) is Leslie Megahey's 2-hour interview with Orson Welles, which covers the Wellesian waterfront, including moving recollections on the curtain call for the1936 Voodoo "Macbeth," when the Harlem audience was so deeply stirred by what they had just seen, they charged the stage and embraced the cast. "That," murmured an emotional Welles, "was magical."

Orson Welles at the Cinémathèque Française (France, 1982; Guy Seligman, Pierre-André Boutang) along with Filming the Trial (Orson Welles, U.S., 1981) and Filming Othello (Orson Welles, U.S./Germany, 1978) display Welles as the profoundly knowledgeable prof: in general, paternal and patient; at times, evincing a gentle melancholy that can quickly turn with a quip. The first two are wide-ranging conversations with film students, the third a film shot for German television in which he relates the benighted history of the making of his Othello. Asked by a student at the Cinémathèque how he hoped to be remembered, Welles declared his indifference: "Posterity is as big a whore as present fame." True enough. But it does not make any less true the unforgettable epitaph he offered in F for Fake a decade earlier, contemplating the cathedral at Chartres and its implicit testimony to the ultimate evanescence of everything: "Our songs will all be silenced. But what of it? Go on singing."

Films completed by Welles

When speaking of Orson Welles' "completed films," it must be with a rueful qualifier: While the films were indeed completed and released, the release print did not always correspond to his intent, and sometimes even contravened it. This was sometimes a result of studio interference, and sometimes due to logistical complications requiring him to be in two places at the same time--a feat of legerdemain even an accomplished magician like Welles could not perform. Usually it was a mixture of both, with the first an unhappy consequence of the second. The Magnificent Ambersons, Mr. Arkadin, The Stranger--who wouldn't wish to see them as Welles meant them to be seen?

While films such as Kane, Ambersons, Touch of Evil, and Chimes at Midnight have become legends in their own right, serving as landmarks and even models for other filmmakers, only two of these--Chimes and Kane--emerged essentially unscathed by studio scythes. In the less exalted regions of the Wellesian cinematic oeuvre, we find the thriller Journey into Fear, which Welles himself once said looked as though it had been edited by a lawnmower.

But what if there was an alternate reality: a version of Journey lost to the dustbins of time, and representing, as with Ambersons and Arkadin (about which more below), Welles' intentions? Out of the blue came one of the stunners of the festival, thanks to one of the denizens of the Web's indispensable Welles resource Wellesnet, and the Munich Film Museum.

A new print of Journey from Germany, which may have been seen previously on German TV without anyone's realizing its significance, was screened on the festival's second day. While Welles scholars are still assessing its provenance and import, a quick run-down of how it differs from the one familiar to U.S. audiences should stir any film buff's curiosity: 1) an establishing shot of a map situating the story in Istanbul, giving it immediate context; 2) replacement of the narrator (Joseph Cotten) by narrative--i.e., by storyline and action; 3) more meaningful character and plot development; and 4) a more humorous tone in general, including the end of the film, which changes its entire timbre.

A second welcome surprise accompanied the screening of the other acknowledged masterpiece in the Welles canon; one that, like Kane, reflects his directorial vision, but unlike Kane--and more in line with his uncompleted films--has been a victim of post-production ills that continue to bedevil it, even decades after its release. According to the festival paper Pardo News, however, these difficulties may at last be nearing resolution.

Chimes at Midnight, Welles' favorite among his filmic offspring, had a troubled history from the start, encountering financial difficulties during the shooting, and proceeding to a tangled web of rights issues that have kept it from being distributed for the last several years. In what is hoped will signal the beginning of the end of its limbo, Chimes was screened in Locarno to an appreciative audience, thanks to the indefatigable efforts of the producer's wife. "I hope that this exceptional screening will mark the beginning of the unknotting of all the ties imprisoning this great gift from Orson Welles to our cinematic heritage," wrote Adriana Saltzman. Indeed!

"Knotted ties" does not, unfortunately, begin to do justice to the tangled web of Mr. Arkadin, its multiple iterations immortalized in Jonathan Rosenbaum's The Seven Arkadins. Here again, thanks to a member of Wellesnet who screened his reconstruction-in-process, attendees were able to see what Welles may have envisioned. Leave it to say that for this Wellesian, it was the first time "linear" wasn't an adjective that could be used to describe everything the film wasn't. For the first time, the story made sense --more in terms of action, perhaps, than motivation; but it was certainly a start. And after all, for Welles, dramatic ellipsis was key to character: a key that does not unlock, but--as the one he made disappear and reappear for the little blond charmer in F for Fake --whose value lies in its ability to make us realize the vanity of trying to "understand" another on our own terms.

Of all his films, The Magnificent Ambersons is one whose mention alone can bring tears to a Wellesian's eyes (and not just a Wellesian's). Sent to Brazil in 1942 as a goodwill ambassador to the Southern hemisphere by the U.S. government during the making of Ambersons, Welles--thousands of miles away, unable see the daily rushes and communicate with his actors and crew in real time--almost unavoidably, lost control of the film. The resulting debacle changed the course of his career in Hollywood, where for all intents and purposes, he no longer had a place, and sent him abroad, where he found a second cinematic home.

For its part, Ambersons stands as a mutilated masterpiece, wistfully (and wishfully) reconstructed in the books of scholars and in storyboards faithfully rendered on DVD--and now in cinematic form, thanks to the dedicated, imaginative efforts of one Roger Ryan (who also, it should be noted, was responsible for the discovery of Journey, above). Using a range of materials in several media--film, storyboard, stills, radio, cutting continuity, oral and written testimony--an effective pastiche was assembled, giving attendees the unprecedented opportunity to envision what Welles's Ambersons would have looked like, using more than their imaginations.

Uncompleted Welles films

The Deep ... It's All True ... Don Quixote ...The Other Side of the Wind ... The names themselves could serve as intertitles for a film about the uncompleted films of Orson Welles. It does indeed get "deep" amongst the claims and counterclaims, financial transactions and inactions, professions, confessions and obsessions. Whether or not "it's all true" must be left to the judgment of the individual observer; logic would suggest at least a smidgen of skepticism. And of course, for Welles, making these films on shoestring budgets, with unpredictable, unproductive producers, crossing continents and decades--ultimately, and with tragic irony, was a consummately "quixotic" quest. As for when we will at last see them as Welles would have wished: the answer to that, lies on "the other side of the wind..."! That said, the workshops on these films were wonderful--so wonderful that, in the time-honored show business tradition of saving the best for last, you'll have to wait until the next installment of this article.

TV programs by Welles

The unexpected variety and abundance of Welles' work for the small screen was deftly delineated on the big one at the Welles retrospective.

Orson Welles' Sketch Books (Great Britain, 1955) were 15-minute programs, made for British television, in which Welles would draw charcoal sketches on a large white pad and use them as the basis for a story he would then relate. Ranging from the unsettling to the horrifying...

... from the magic of "idiot boards" that make political hacks sound like Ciceros, to the magic of Houdini ringing church bells across the square without lifting a finger (but raising a hand--to signal his wife to pull the cord) and...

... from tales of reactions to "War of the Worlds," and true confessions regarding his innocence ("...we wanted people to understand that they shouldn't take any opinion pre-digested, and they shouldn't swallow everything that came through the tap"), to trenchant and humorous observations on doing business with the government (that thankfully, ring less true today with the advent of e-gov)...

The Sketch Books, which traded on being up-to-date in 1955, still drew chuckles, gasps, and knowing nods from their audiences, a half-century later.

Orson Welles Talks with Roger Hill (U.S., 1978) was a once-in-a-lifetime look at Welles' conversations with his beloved Todd School mentor, who was, Welles tells him, unknowingly responsible for Orson's career: to get the attention of the man who was also the school's athletic director, the athletically hopeless boy pulled out all the stops in every area in which he had any talent or interest. The spark was struck with "theater" the rest is history...

The Golden Honeymoon (U.S., 1970) was shown in a combination of film and radio program, making it the first time the entire story as realized by Welles would be seen. The videotape fragments were bridged by Welles seated in front of a stained-glass window reading the story in the voice of the old man and audiotape excerpts found among the Film Museum's Welles materials.

Orson Welles' Shylock (U.S./Italy/Spain, 1938-1973) was a revealing, and at times haunting, collage of existing footage of the "Merchant of Venice" project that Welles pursued throughout his career in both radio and film. Even on the "Dean Martin" show, his respect for his audiences was no less than on film, his portrayals as rich and multi-layered.

The same can be said for his Lear portrayals ("King Lear," U.S., 1953, 1956, and 1983; with Andrew McCullough), which included a turn on "The Ed Sullivan Show." (Though it was a bit mind-blowing to hear Alistair Cook cheerily plug "Scott facial tissues, with wet strength added" as the heartbreaking play's curtain fell.)

And then there was "The Hearts of Age" ... "Paris After Dark" ... "In the Land of the Basques" ... "London" and "Orson Welles' London" ... "The Spirit of Charles Lindbergh" ... "In the Land of Don Quixote" ... "F for Fake" trailer ... "Orson Welles' Vienna" ... "Viva Italia" ... "Orson Welles' Jeremiah" ... "The Dominici Affair" ... "Return to Glennascaul" ... "The Orson Welles Show" ... "Orson Welles on Stage in Dublin" ...

TV commercials and programs with Welles

Perhaps because they did not fit easily into one of the larger categories, and were not numerous enough to stand on their own in two separate ones, Commercials & Specials were grouped together. Yet they could not have been more formally or thematically dissimilar. Occasionally a connection sneaked its way in, making one marvel anew at Welles’ endless inventiveness.

We laughed and cringed, seeing the great man hawk whiskey in Japan and compare making spirits to making films, then swallowed our smartness as he quietly inserted a plug for one of his films. We tipped our hats to the programmers as his ads for sherry segued smoothly to a segment of him making up for Falstaff, explaining the story as he went along in terms even a child would understand ("a great-great-grandfather of all the flower children... he was a bum, a beautiful bum") and noted that Falstaff’s "[sherry] sack was fortified with booze." Take that, you snobs!

To be continued in November.

Thumbsucker: An Interview with Writer/Director Mike Mills, Actress Tilda Swinton and Actor Lou Pucci

By Michael Kyrioglou, DC Film Society Director

Michael Kyrioglou: Your film was very bizarre, I loved it. Your background is very diverse--skateboarding, graphic design, video and commercial work. This seemed like a good story with a quirky edge that was right up your alley. What in the source material drew you to it?

Mike Mills: To me it’s because it was so mainstream and normal --these are problems that everyone has, there’s not really anything odd or exotic, it’s almost banal. And we tried to tackle it that way--these are things that just don’t happen to other people, these things happen to us too. With all the things I could have done, it seemed like a good choice. Nothing in particular about being a skater or graphic artist really drew me--it was more of being a kid, a human, a dog owner. Just being ordinary. Ordinary People was a huge influence on the movie. To me, being weird is its own little weird ghetto.

Michael Kyrioglou: The majority of the population would look at a film like this and think it’s a little bizarre I think--because it’s taking a non-mainstream view of things.

Mike Mills: I have to go door to door and disagree with all of those people. It's different from those films. Like Ghost World or Donnie Darko, these kinds of films. It’s more boring, more normal, I honestly believe that. Ghost World is a little more arch. To me the Donnie Darko comparison is a strange one.

Michael Kyrioglou: Maybe it’s because they all have young protagonists through which we view the story. There are small similarities.

Mike Mills: And ultimately, the audience is always right with what they think.

Michael Kyrioglou: Was Walter [Kirn] ever going to adapt his own novel to a screenplay?

Mike Mills: Not to my knowledge at all. And he was kind of beautifully Buddhist about it… it's about his life and his mom and all. He was the first to tell me ‘you’re going to have to let go of the book.’ He was a great teacher to me and a really nice guy. When someone has so much at stake, it was amazing how much he just let go. It was important that he was ok with it because he just gave the book to me. He was more like a writing teacher than anything else.

Michael Kyrioglou: Was he on the set and involved?

Mike Mills: He came to visit and was excited about it.

Tilda Swinton: He’s in it. He’s one of the debate judges.

Michael Kyrioglou: Did you, Tilda and Lou, want to ask questions of him, about the characters?

Tilda Swinton: The book and the screenplay are related, but they’re separate, they’re distant cousins.

Lou Pucci: And he was such an old Justin (Pucci’s character). He was awesome and strange and so completely Justin.

Mike Mills: One funny thing happened, in relation to Keanu’s (Reeve) last scene where he’s talking about ‘none of us really knows what we’re doing, what’s so wrong with that’--Walter’s at my house and I was doing my best crying director impression, the woes of life. And he started talking to me about how there are no easy answers, we’re all just guessing in the dark, what’s so wrong with that, it's just human, if you have all the answers then you should be worried. Then I said, ‘whoa Walter, can you say all that again’ and I wrote it all down to use.

Michael Kyrioglou: Lou, I am also from Central New Jersey like you are. This is a big year for you with this film winning awards at the festivals and opening, as well as The Chumscrubber, and HBO’s Empire Falls. What are your thoughts on it all? You seem very well-adjusted and unaffected by it all. Are you enjoying it?

Lou Pucci: Yes. It’s just kind of funny. I could have been going to college right now, but this is a lot more interesting. I was supposed to go to school for visual arts, for editing. Now I know I would have never made it and stopped half-way and started doing something with directing or writing. I couldn’t sit in front of a computer for that long. And that’s why Mike let me sit in to watch all the editing, to get to see all the different phases of the film as it developed.

Michael Kyrioglou: I read that you liked to work with a lot of improv work to prepare. I know some actors love improv and some hate it.

Tilda Swinton: The actors who love it are people like us who can’t remember our lines. That’s the great advantage in my book, you make it up, and you don’t have to learn any lines.

Mike Mills: But they’re also really good at it.

Michael Kyrioglou: Did you try to record any of that rehearsal and use it in the material or how a scene was done?

Mike Mills: Definitely, some of my favorite scenes are ones they improvised and that I jotted down. To me it’s most exciting when they don’t quite know what they’re doing, that’s the stuff you want to film.

Tilda Swinton: It makes me very impatient to be working with a finished script. It’s really quite intoxicating to… I hesitate to use the word organic, it’s so misused, just sort of everything is fraying so that means that you’re actually alive. When I first met Mike, I think we talked a little bit about the story of the film, but we talked more about the atmosphere of braveness that we were both interested in and that designated how we worked. I have this very clear sense that we did what I have always wanted to do which was that we only moved on from a scene when we kind of felt uncomfortable. If anyone said “got it” then we sort of felt like we had to do it again.

Michael Kyrioglou: It all feels very of the moment and natural, which is great. It comes through. I like a lot of Mike Leigh’s stuff where he actually films the improv scenes based on particular parameters of lines or scenarios.

Tilda Swinton: And he works in a similar way. His actors improvise and he writes it into an actual script.

Michael Kyrioglou: Something we talk about a lot in discussions when filmmakers are here…

Mike Mills: Money.

Michael Kyrioglou: …that too, but the time frame to get a film made. How long was the process to getting this film made?

Mike Mills: Six years. I started in 1999 and we shot in 2003. So it took a long time, for me it took awhile to write as it was the first time writing something. And then the real fun part was trying to get money for it. Going around to every production company, including the one currently distributing it, and they all said no. It was a year and a half of going door to door and being told no. And then simultaneously in the actor world it’s having a different life where you’re hearing more yes answers.

Michael Kyrioglou: I guess it’s all about connecting with the right person at the right company at the right time--and who connects with the material.

Mike Mills: And the company who ended up financing us didn’t even exist when I started the process.

Tilda Swinton: And Lou Pucci wasn’t even born yet!

Michael Kyrioglou: You were doing The Sound of Music on Broadway at that point, right?

Tilda Swinton: You were in a pair of lederhosen my friend!

Lou Pucci: I was a freshman in high school I think when I did that. I was this kid in New Jersey, doing some writing, masturbating wildly.

Michael Kyrioglou: Tilda, I read that you had a break during the filming of the Narnia film, The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe and did a role in Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers.

Tilda Swinton: Indeed. I went from New Zealand to New Jersey and back.

Michael Kyrioglou: Do you like that, overlapping material or is it distracting?

Tilda Swinton: I have to admit I have never done it before. It was an adventure. But it was possible for those two films because they were so different. It was a delight for me to go from this enormous film--making a big, big film like that is like working on a war, you’re going to the set by helicopter--you know to go from that to a tiny little film was like going home for a breather.

Michael Kyrioglou: I wonder how much of your own personal awkwardness you brought to the character of Justin. Everyone in the film is dealing with being uncomfortable with who they are and striving for something else.

Lou Pucci: I always felt like I was being really serious on the set and that’s how Justin feels. I really felt like how the character of Justin was whenever when I was on the set--he always felt like he was too serious and he was trying to find the right thing and he couldn’t figure that out--and that’s exactly what I was dealing with. I had no idea what I was doing, I was the lead in this movie, I just wanted to do a good job and there are no real answers for that. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, but that’s what the movie’s about.

Michael Kyrioglou: You had a great cast for this film with Vince Vaughn, Keanu Reeves, and Vincent D'Onofrio. It felt like a real ensemble, the smaller roles felt necessary and not just cameos.

Mike Mills: Everyone was really nice and very respectful to me, more than they needed to be.

Tilda Swinton: Certainly when they were in front of you.

Mike Mills: I lucked into a bunch of super kind generous people. And no one messed with me. There’s usually this guy on guy joking thing, but no one did anything.

Tilda Swinton: And I think it’s partly the material. You have to be drawn to it, to want to be a part of it.

Michael Kyrioglou: The actors will get you on the next project! What’s next for everyone?

Tilda Swinton: I’ll be working on something with a Hungarian director in the autumn, and then with Mr. Mills again.

Mike Mills: I am working on a new script that Tilda will be in. Another thing about families.

Lou Pucci: I’m doing Southland Tales. I’m playing a strange part which is why I dyed my hair. It’s going to be really good. The guy who did Donnie Darko is making it.

Michael Kyrioglou: You seem to e

njoy being together again for this p.r. tour and hitting all the film festivals. It’s been awhile.

Lou Pucci: I just want to do films with them.

Tilda Swinton: We’re linked for life. This is it.

Michael Kyrioglou: Like something from another era--actors, writers and directors forming a production company. An excellent idea. Thanks!

The 32nd Telluride Film Festival

By Nancy L. Granese, DC Film Society Member

Another Labor Day, another trip to the Telluride Film Festival in Telluride, Colorado. How lucky can a person get? Maybe it’s just the impact of too little oxygen at 10,000 feet, but Telluride is really as good as it gets. It’s the only place I know where standing in line for a movie is actually fun and often educational. It’s still the kind of place where, because of Ken Burns’ ongoing support for the TFF, attendees get an early look at major PBS events: this year’s surprise screening was a four-hour showing of Martin Scorsese’s Dylan documentary a month before its broadcast.

Still, this year’s honorees seemed quirkier than usual. Sure, it makes sense to recognize the people behind the Criterion Collection DVDs and Janus Films. But who came up with the team of Charlotte Rampling and Mickey Rooney? This year’s Guest Director was novelist and playwright Don DeLillo, in keeping with the TFF’s tradition of picking non-traditional Guest Directors. Virtually every film was accompanied by its director, and the actors included William H. Macy, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, Helena Bonham-Carter, and Aaron Eckhart, with Andy Garcia and Liev Schreiber each introducing their directorial debuts.

Several themes this year: films were serious, and none could be called outright comedies. The musical scores of several were just terrific: Le Pont des Arts, Everything is Illuminated, Edmond, Capote, Breakfast on Pluto, and Walk the Line in particular. Every film seemed to be perfectly cast and the acting was uniformly excellent. The final theme is the result of what I think is the film directors’ caving in to the special effects guys (“let’s show it because we can!”): throat slashings, which kept showing up at the most unexpected moments. Please stop.

The Films

Bee Season, based upon a novel by Myla Goldberg, is one of those movies that makes one ask, "So how did this get made?" The snarky person behind you on the way out says, "Richard Gere." There is the sense that Gere read the book or the script, liked its mystical qualities (I'm guessing here since I haven't read the book), and that was all it took to attract the money. Or maybe it was Arnon Milchan, one of the producers. At any rate, TFF-goers who'd read the book didn't like the film any better than I did, a primary complaint being that the book's leading characters (the Naumans) are frumpy failures living through their children. Certainly it’s difficult to see either Gere or Juliette Binoche as frumpy anythings. Binoche in particular still has that internal glow thing going on and while someone of her beauty and power might well be married to a Gere-like professor, it's difficult to believe that such a woman would behave as oddly as her character does. The film has nothing to do with apiaries: it's about the season of the school year when children participate in spelling bees (Spellbound [the 2002 documentary] carries some of the blame for this). The family's young daughter stumbles upon an unexpected ability to spell virtually anything, in part because of a mystical connection she makes with the words themselves--she has some Tim Burton-esque moments when everything around her comes alive, including the tiny flowers on her blouse. But all is not well at home as her older brother (Max Minghella--the director's son--very fine, and likely to have a genuine film career) feels himself shunted aside by Dad and so takes up with the Hare Krishnas. Dad devotes all his time to little Eliza (Flora Cross, very good, with just the right balance of flaky sweetness and self-effacing genius) and decides she's a true mystic who will understand the Kabbala. Mom has a strange hobby that not unexpectedly causes the Naumans to implode. People who've read and enjoyed the book may provide a built-in audience, but I don't see that the film will reach much further.

The absolute best film I saw was Brokeback Mountain, and it was the favorite film of anyone who saw it. You've heard of it as the "gay cowboy movie" which dramatically undersells the beauty and passion of this wonderful film. Heath Ledger, who did good work in Ten Things I Hate About You, but not in much else, is terrific. Jake Gyllenhall, whose work has been noticed by critics and pre-teen girls alike, is equally good. The two play young cowboys who meet and bond one idyllic summer as they baby-sit a herd of sheep on the mountain. They then go their separate ways--more or less--while staying in touch over the next twenty years. It's a very simple story. But nothing can prepare you for the impact of this film. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana have written a script without a single superfluous word and many constructive silences. Ang Lee's direction, greatly enhanced by Rodrigo Prieto's gorgeous photography, is perfect. According to the film’s production notes, all of Lee’s films are about the dynamics of family and other intimate relationships, but nothing he’s done before prepared me for this, especially since I thought Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon was wildly overpraised. This film is brilliant: engaging, moving, touching and beautiful. Bring your hankies.

Paradise Now is a truly international film as companies from France, the Netherlands, Germany, Israel, and the EU and World Cinema Fund are all producers, while the US distributor is Warner Independent. As with so many other films, the glib summary of this one--“a sympathetic portrayal of suicide bombers”--sells it short and will scare off some of its audience. It’s a very good film, but relentlessly grim because it is so clearly headed to a sad, infuriating end. Two young men, childhood friends, are called upon to make good on their promise to become suicide bombers. The taut 90-minute film covers their last hours at home, where one gets the sense that each young man’s family has a sense of what he’s about to do, but everyone seems willfully to look the other way. The only mildly pacifist voice is that of a young woman who’s been educated “in the West” but who has returned to Nablus to play a part in achieving peace for her people. But while her arguments make an impression on Said (Kais Nashef), it’s too little way too late. The character of Said is so well written, so well acted, so genuine, that one can’t help truly hearing his frustration and even understanding and sympathizing with it. In one lengthy speech near the end of the film, Said tries to explain to his Palestinian overlords why he feels he must do this horrible thing, and even though I freely admit to a personal view that suicide bombers are pure and simple murderers, Said’s impassioned justification touched me. An intense experience, not to be missed.

One of the best things about going to a film festival is that you get so much information from your fellow line-sitters (or -standees). Other than Brokeback Mountain, Caché was the most discussed film this year. Without question, this is Daniel Auteuil’s film--the director and screenwriter, Michael Haneke, won the Director’s Award at Cannes, and I hope he thanked the actor. He and Juliette Binoche (in a far more believable role than that in Bee Season) play a well-to-do soigné Parisian couple who are confronted with surreptitious surveillance of their home, the confrontations taking place in the form of videos dropped on their doorstep. The police are unhelpful, the enclosed pictographs become increasingly macabre, and Auteuil becomes increasingly desperate as he tries to read the clues in the videos to figure out who’s doing this to him and his family and why. It’s a brilliant conceit, a tight two hours, with a completely unexpected dénouement. The best advice we received from those who’d seen the film before we did was: Pay Close Attention. I’d add, Right Up To The Very End. It took six of us twenty minutes of discussion to figure it out. Terrific.

By the time you read this, Everything Is Illuminated will have opened. Another iffy book-to-movie, this got mixed reviews from those who’d loved the book, and even from those who hated the book. I think the story of a rich young American looking for his Ukrainian roots put off some viewers--this was one of several Jewish-themed movies and too many can be a downer. Then there was the anti-Frodo contingent: while Elijah Wood is clothed in a (increasingly) rumpled suit, he still seems to be a Halfling, only rather less animated. Those eyes! In a post-screening interview, director Liev Schreiber admitted to being “obsessed” with Wood’s eyes and said that he had the actor wear glasses to magnify them. Not surprisingly, Wood could hardly see and walked into walls and furniture; eventually, he was given contact lenses to compensate for the extreme distortion of the horn-rimmed glasses. Yet Wood’s blankness isn’t always helpful to the film, most of which is taken up by his search for the Ukrainian woman who saved his father’s life in World War II. The greatest pleasure of the film (aside from a justly praised sunflower setting) is Eugene Hutz’s performance as Alex, Wood’s local guide. In reality, Hutz is the front man for a self-described “Ukrainian punk rock gypsy” group, “Gogol Bordello”, that Schreiber interviewed in his search for the right music for the film. At some point in what sounded like a lengthy, not quite sober discussion of music, film, and the Ukraine, Hutz leaned across to Schreiber and said, “You know, I em thet guy.” Schreiber agreed and hired him. Hutz had never acted before, and certainly not before a camera, but Schreiber said he worked very hard--and it paid off. Hutz makes the infuriating Alex enormously funny and even endearing, no mean task: if you’ve ever traveled overseas, alone with a local guide whose imaginative command of English does nothing to help you understand where you are or what you’re seeing, you get the idea. He pulverizes English in every sentence, and yet manages to make himself completely clear. He is a genuine character, who bullies his driver (his not-really-blind-grandfather), his client, and complete strangers to fulfill his responsibilities. It’s unfortunate the rest of the film isn’t up to Alex’s standard.

The other crowd-pleaser at the TFF was Walk the Line, the Johnny Cash biopic. Likely to be touted as this year’s Ray, it’s a much better film. Ray made its way on Jamie Foxx’s superb performance, but it was fundamentally flat. Walk the Line is a much richer film, not least because Joaquin Phoenix’s heartfelt portrayal of Cash is balanced by Reese Witherspoon’s feisty portrayal of June Carter. Both he and Witherspoon do their own singing and playing and it adds a certain resonance to their entire performances, not only the musical riffs. Director James Mangold opens the film brilliantly, with Cash waiting to perform at Folsom Prison. The bleak surroundings, the Man in Black, and the barely controlled, but not quite suppressed, violence of roaring inmates demanding to be entertained is as energizing as a good opening should be. Mangold doesn’t waste much time getting to the music, and fortunately avoids the egregious error of introducing a much-loved song and then segueing to another scene; instead he lets Phoenix and Witherspoon sing almost completely through each one, which is really what audiences want. And the scenes from Cash’s first big tour (actually a series of one-night stands) with a group of other newcomers named Elvis, Waylon and Jerry Lee, is both quaint (they carried their instruments and personal belongings in their own cars, in a ragtag caravan across the South) and hilarious, one of the film’s highlights. My only complaint was the use of transparent and awkward references to introduce songs: for example, Witherspoon, resisting Cash’s advances, saying “It burns, it burns”--which fortunately resulted in “Ring of Fire”--is rather corny. But that’s a genuinely minor quibble. The movie is first-rate.

In the late ‘80’s, Janet Malcolm wrote a piece in the New Yorker called “The Journalist and the Murderer.” In a riveting opening--“Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse”--Malcolm took on Joe McGinnis, who had made a fortune out of his book Fatal Vision, about a young Army officer who murdered his pregnant wife and two young daughters. The officer was convicted of all three murders, and later sued McGinnis, claiming that the author had persuaded him to cooperate by pretending that she would write a work vindicating the young father, not condemning him as a heartless, amoral killer. Malcolm could just as easily have been writing about Truman Capote, who reinvigorated the literature of true crime with his 1965 masterpiece, In Cold Blood. The story of how Capote, a darling of the New York intelligentsia in the late ‘40’s and ‘50’s, “preyed” on the “vanity, ignorance and loneliness” of two young murders is the subject of the very dark film, Capote, written by, Dan Futterman, who is better known as an actor (TV’s Judging Amy and Robin Williams’ son in The Birdcage). Futterman’s high school classmate, Bennett Miller, directs, and he does a competent job of placing the film in both New York and Kansas, the setting for the vicious murders that prompted Capote to head west, dragging along his “research assistant” Harper Lee (portrayed by a very engaging Catherine Keener). Another longtime Futterman friend, Philip Seymour Hoffman, plays Capote. I’ve always considered Hoffman to be a talented young Santa, but he is amazingly slimmed down and downright tiny in this film while still dominating every moment. I kept thinking of Janet Malcolm, and also Ed Harris in Pollock--the crazy talented person who is driven by innate talent that controls the artist rather than the other way around. Capote qualifies as one of those movies that are sometimes called “prestige films”--the supporting cast is filled with recognizable performers: Keener, Chris Cooper, Bruce Greenwood, Bob Balaban, while two of the major roles, the murderers Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, are played by excellent actors that you think you’ve never seen or heard of until you look them up on IMDb and find out that each has been in forty-plus movies and numerous television shows. The film is successfully evokes the cultural and media differences between today and late 50’s Middle America, while simultaneously providing a view into a committed gay relationship that is utterly contemporary. It’s well worth seeing, but it’s not an up evening.

There’s always one delightful surprise at the TFF, and this year’s, for me, was Breakfast on Pluto, the latest from Neil Jordan. Cillian Murphy, who’s played minor roles in big films (Cold Mountain, Girl with a Pearl Earring) and big roles in minor films (Intermission), as well as having his share of hits (28 Days Later, Batman Begins and Red Eye) is lovely and amazing as a young Irish orphan who loves live, laughter and cross-dressing. It’s a Neil Jordan film, after all, so there is the obligatory IRA encounter that turns ugly, but the story of Patrick Braden (Murphy), who prefers to be called “Kitten” and who doesn’t want to be pestered by anything “serious”, is that of the triumph of naïveté over ignorance, indifference, and bastardy. This is another film with a superlative cast: Liam Neeson, plays a local priest who looks out for Kitten, the always wonderful Stephen Rea, Brendan Gleeson, Ian Hart, Ruth McCabe and others from Jordan’s irregulars. There’s a touch of magical realism (chattering robins), kitchen sink drama (it’s Ireland in the 70’s after all) and swinging London where Kitten goes to find his mum, whom he calls “Phantom Lady” in a hushed and worshipful tone. The screenplay, written by Jordan and Patrick McCabe from McCabe’s book is funny, profane and delightful. A must for Jordan fans, Murphy fans, and anyone who’s not put off by cross-dressing. Just a wonderful film.

Demonstrating my ignorance, I’d never heard of Eugène Green, a French filmmaker honored by the showing of three of his films at this year’s TFF, his first at an American film festival. But wait, he was born Eugene (sans accent grave) Green in NYC in 1947, moved to Paris in his 20’s, and looks like Gabe Kaplan. Does that make a difference? Are his films really French? The film I saw, Le Pont des Arts, presented parallel stories of a suicidal young man and a talented young singer working under the direction of the most malignant impresario one could imagine. The film is in a mix of many things: satire, tragedy, surrealism, magical realism, and melodrama. Despite the presence of several stereotypical “French cinema” characters and situations, I found the film engrossing, not least because of the glorious performances of several Monteverdi pieces--the actors did a barely acceptable job of lip-synching, but no worse than Ashlee Simpson. Chief among the stereotypes is the self-important sadistic Guigui, who is introduced as an elegant, charming gay man, devoted to precious things. His most impressive quality, it turns out, is his use of inventive, lacerating invective, a questionable coaching technique for his youthful singers. Not surprisingly, his talented soloist cracks. However, because her collapse occurs after her group’s first album (yes, they still seem to have records in France--although perhaps I missed a clue regarding the period in which the film was set) is released, her magnificent voice restores the young man’s interest in life as her interest declines. There’s a bit of Laura in the film--think Dana Andrews’ fascination with the portrait, transposed into an LP of Monteverdi, and you’ll get the idea.

Another unexpected surprise was Conversations with Other Women, starring Aaron Eckhart and Helena Bonham-Carter. Two people meet a wedding. She’s the bridesmaid he’s been eying throughout the evening, and it takes him a while to strike up the conversation. The film is about where the conversation goes and why. I really enjoyed this movie--Eckhart and Bonham-Carter are very very good and completely believable. Everyone’s been to one of these weddings and most of us have been through a similar experience, up to a point. The director, Hans Canosa, has only made one other film (Alma Mater, which won the audience award at the Austin Film Festival), and he’s still experimenting. The experiment in this film, which many found off-putting, but which didn’t bother me, was a split-screen in every scene. I found it a realistic approximation of real life when our eyes constantly shift from one person to another in conversation. Instead of being forced to focus on the director’s/editor’s point of view, there was a choice to make--watch her? watch him?--that made the film more engaging. The bad news is that less talented directors, with less interesting stories, will now use the technique and there will be some very bad movies to avoid. But not this one. Well worth seeing.

I guess there always has to be one movie that I hate or that disappoints, even at Telluride; this year it was Edmond. I was excited to see it because I’m a devoted David Mamet fan, and it had William H. Macy, Julia Stiles, the incomparable Joe Mantegna, and of course, Rebecca Pidgeon, Mamet’s current wife. (Or is she? Mamet was quoted as saying that he wrote this play while his marriage was breaking up--but which one?) Macy again plays an unhappy, sad-sack married man who tells his wife he wants a divorce. She throws him out and he wanders the streets seeking sexual solace from the likes of Mena Suvari, Bai Ling, and Denise Richards, and finding violence. After the screening, there were questions about the extreme violence in the film. I found Macy’s answer to the questions more disturbing than the film itself: “It all feels true. I don’t know why or what it means, but it feels true.” True? Time to leave.

A Korean film The President’s Last Bang, by Im Sang-soo, is the recreation of the 1979 assassination of South Korea’s long-time dictator Park Chung-hee. It’s bloody. It’s violent. I liked it. As Park’s regime was winding down, he was murdered by the head of the Korean CIA, a one-time ally. Like all good stories, there’s humor amid the gore, and even pathos. The movie should do well in Washington if it gets here. We provide the perfect audience for a film about political hacks, covert operatives, military goofballs, trashy sweeties and big fat “security” guards coming together in a perfect storm. There are even innocent victims so that we can all wring our hands about collateral damage. Even better, the killers get justice and new bad guys take over. The film’s tone is Dr. Strangelove directed by Sam Peckinpah. If you can take the gore, you’ll enjoy it.

It sometimes seems that a festival cannot be worthy of its name without at least one Holocaust film and the 32nd TFF had at least two (that I saw), with a handful of others about the suffering that still defines this nation’s view of the Middle East. Fateless, directed by Hungarian cinematographer Lajos Koltai (known for his many films with Istvan Szabo), is a well made movie, but, like most such films, exhausting and painful to watch. How does one eat popcorn while watching the agonies of Buchenwald? More interestingly, what continues to bring audiences to these movies? Is it simply the urge to bear witness, to extend belated respect for all those Jews, those gypsies, those homosexuals, those “defectives”? Or is it a questionable voyeurism endemic to the human animal? I can’t say, but Fateless seemed to me to appeal more to the latter, unpleasant, need. The film follows a teenager in his journey from Budapest to several different camps. The performance of Marcell Nagy makes young Gyuri’s suffering is so graphic, so specific, so genuine, that it’s virtually impossible to distance oneself from the film. It’s an excellent film, but really too much.

Among last year’s animated short films at Telluride was the eventual Oscar winner, Ryan, which helped me win the office pool. This year, Telluride showed this year’s student Academy Award winner, 9. What a touching, charming film! It’s the story of little beings made of scraps of fabric and the detritus of a mechanized society, who nonetheless have souls. I certainly hope the director, Shane Acker, gets a shot at making full-length features. If any of them are half as good as this little masterpiece, we’ll all be lucky. Short films are beginning to be released in collections on DVDs, and this one should achieve whatever standards are set to make it into release. At a minimum, 9 certainly should be shown in place of the rotten ads and even the Stella d’Artois films that haunt our theaters today. Look for it.

Other shorts struck me as being more about technique than story, not necessarily a bad thing. Apple is a new sponsor for Telluride and the three other shorts I saw were all heavily dependent on digital technology. While Darwin Sleeps and Spacer were actually a compilation of digital photographs--eye candy, surely, but they left me cold. The third, City Paradise, was a surreal look at London through the eyes of a young Japanese woman, which lost me when it moved beneath the earth’s surface. Just OK.

A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929), made by Anthony Asquith, a fairly successful British director whose career spanned nearly forty years, was the lone silent offering this year. It’s the story of a young woman with two suitors and not surprisingly, she chooses the wealthy sophisticate instead of the humble barber. The barber takes it badly, mayhem ensues, but she and her new husband manage to forgive him in the end, though they can’t save him. The film is dated, the acting is stagy, and sometimes the story lags, but it still managed to be suspenseful and touching. The camerawork, particularly when the action moved to the moors, was brilliant, and I was reminded of how satisfying black-and-white films can be. And the live piano accompaniment doesn’t hurt, either.

Another animated screening was The Moon and the Son + Much More, by Jonathan Canemaker, a much-honored NYU professor, who’s both a writer and filmmaker. The Moon and the Son is Canemaker’s personal story about coming to terms with his violent, edgy father. Without sliding into self-serving pity, the film--a short, really--deals frankly with Canemaker’s difficult childhood, his repugnance toward his father, and their eventual reconciliation. I’ve made it sound too hokey, but in fact, it was a very powerful film. Canemaker then introduced the Much More--seven animated shorts covering the giants of animation from Winsor McCay (Canemaker is McCay’s biographer) to a final film by Len Lye, Free Radicals. The seven films were made between 1918 and 1958, and one does get the sense that this presentation will appear as a DVD someday. Lye’s film, which he made by scratching a needle onto film stock, is brilliant.

If you go...

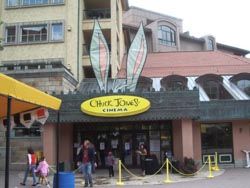

There are several ways to attend TFF. There are several levels of passes, the least expensive still costing $325, the most expensive being tied to serious underwriting of the festival. The $325 pass gets you into every film at the Chuck Jones Theater (photo at left), which is a converted convention centre meeting hall which seats about 600 people. You have to pick up a “W2” (a “Wabbit Weservation”) for each film; W2s are available 5 hours before each showing. You can also attend the Labor Day picnic with the filmmakers and see two films at other venues, but those are at the foot of the mountain, requiring a 20-minute gondola ride down to the main part of Telluride. But if you stay at the Chuck and your butt can take it, you can see as many as 17 films. More expensive passes get you into screenings and events at other venues, and the really expensive passes get you to the front of all lines, and probably some sucking up privileges.

There are several ways to attend TFF. There are several levels of passes, the least expensive still costing $325, the most expensive being tied to serious underwriting of the festival. The $325 pass gets you into every film at the Chuck Jones Theater (photo at left), which is a converted convention centre meeting hall which seats about 600 people. You have to pick up a “W2” (a “Wabbit Weservation”) for each film; W2s are available 5 hours before each showing. You can also attend the Labor Day picnic with the filmmakers and see two films at other venues, but those are at the foot of the mountain, requiring a 20-minute gondola ride down to the main part of Telluride. But if you stay at the Chuck and your butt can take it, you can see as many as 17 films. More expensive passes get you into screenings and events at other venues, and the really expensive passes get you to the front of all lines, and probably some sucking up privileges.

You can also buy single tickets ($20) to individual films, but you aren’t allowed into the theater until after all passholders are seated. Still, many people come to the festival and do that. There are also free seminars each day and free showings of films outside at the Abel Gance Open Air Cinema (see photo above) in a downtown Telluride park each night. There are several scholarship programs for students as well. Or you can go to Telluride the week after TFF and see the most popular films at the Nugget, Telluride’s year-round theater.

You can also buy single tickets ($20) to individual films, but you aren’t allowed into the theater until after all passholders are seated. Still, many people come to the festival and do that. There are also free seminars each day and free showings of films outside at the Abel Gance Open Air Cinema (see photo above) in a downtown Telluride park each night. There are several scholarship programs for students as well. Or you can go to Telluride the week after TFF and see the most popular films at the Nugget, Telluride’s year-round theater.

Calendar of Events

FILMS

American Film Institute Silver Theater

You can still catch the last few films in the series of Latin American films until October 3. Four films from Korea will be shown, including Sam Ryong the Mute (1964) with director Shin Sang-ok and actress Choi Eun-hee in person; the director and his wife were kidnapped and forced to work in North Korea for several years. A series of Samurai Cinema from Japan runs from October 8-November 6, many in brand-new 35mm prints. Also there is a series of French Cinema Under the Occupation, films by Ernst Lubitsch, films directed by Mel Brooks, and films for Halloween. Check the website for other films and special events.

Freer Gallery of Art

The Freer concludes its two-month series of Korean films with Mudang: Reconciliation Between the Living and the Dead (Park Ki-bok, 2003), a documentary about Korean Shamanism on October 2 at 2:00pm; Save the Green Planet (Jang Jun-hwan, 2003) on October 7 at 7:00pm; Women of the Yi Dynasty (Shin Sang-ok, 1969) on October 14 at 7:00pm with the director and actress Choi Eun-hee in person; and The Houseguest and My Mother (Shin Sang-ok, 1961) on October 16 at 2:00pm, also with the director and his wife attending.

"Ten Masterpieces of Turkish Cinema" begins in October with Dry Summer (Metin Erksan, 1964) on October 23 at 1:30pm; Hope (Yilmaz Guney, 1970) on October 23 at 3:30pm; Innocence (Zeki Demirkubuz, 1997) on October 28 at 7:00pm and Mr. Muhsin (Yavuz Turgul, 1987) on October 30 at 2:00pm. The series concludes in November.

The Freer is one of the venues for the 2005 DC Asian Pacific American Film Festival with And Thereafter (Hosup Lee, 2003), a documentary about Korean women who married American GIs after the Korean War on October 8 at 1:00pm; a series of short films from Hawaii on October 8 at 3:00pm; Monkey Dance (Julie Mallozzi, 2004), about Cambodian teenagers in the US on October 8 at 5:00pm; What's Wrong with Frank Chin (Curtis Choy, 2005), a documentary about the author and activist on October 15 at 2:00pm; and a program of short films by women directors on October 15 at 5:00pm.

National Gallery of Art

"Mary Pickford Restored," a series of films starring America's Sweetheart, begins with Sparrows (William Beaudine, 1926) on October 2 at 4:30pm. Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (Marshall Neilan, 1924) is on October 8 at 1:00pm; The Little American (Cecil B. DeMille, 1917) is on October 9 at 4:30pm; and Behind the Scenes (James Kirkwood, 1914) is on October 15 at 1:00pm. All are preceded by short films.

"Cinema Sud" is a series of films from southern Italy, beginning with a program of films by Sicilian Vittorio De Seta on October 1 at 3:00pm, shown with Life Blood (Edoardo Winspeare, 2000). Others are Stolen Children (Gianni Amelio, 1992) on October 8 at 4:00pm; The Passion According to St. Matthew (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1964) on October 16 at 4:30pm; Not Fair (Antonietta de Lillo, 2001) on October 22 at 2:00pm; Sailing Home (Vincenzo Marra, 2001) on October 22 at 4:00pm; and I'm Not Scared (Gabriele Salvatores, 2003) on October 23 at 4:30pm.

Other special events include Diva Dolorosa (Peter Delpeut, 1999) on October 1 at 1:00pm; a program of early avant-garde and experimental films "The Devil's Plaything: Fantastic Myths and Fairytales" introduced by Bruce Posner on October 15 at 3:30pm; Imagining America: Icons of 20th Century American Art (2005) on October 29 at 2:00pm; and A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935) introduced by Jay Carr.

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

On October 6 and 7 at 8:00pm is 4, the debut film of Russian director Ilya Khrzhanovsky (2004). On October 13 and 14 at 8:00pm is El Perro Negro: Stories from the Spanish Civil War (Peter Forgacs, 2005), an award-winning documentary.

National Museum of African Art

On October 2 at 2:00pm is Afroargentinos (2002), a documentary exploring the roots of racism in Argentina. On October 30 at 2:00pm is The Price of Forgiveness (Mansour Sora Wade, 2002), an adaptation of the novel by Mbissane Ngom, followed by a discussion.

National Museum of the American Indian

Short films from Bolivia are shown on October 1 and 2 as part of " El Festival Boliviano," including Woman of Courage (Jose Miranda, 1993) about Gregoria Apaza, who led the 1871 Aymara uprising against the Spanish. Another film program "Native Views" shows various short films on October 9, 14, 15, and 21.

Museum of American History

Taking part in the 2005 DC Asian Pacific American Film Festival is Grassroots Rising (2005) on October 9 at noon followed by two programs of short films at 1:15pm and 3:30pm. On October 16 at 1:00pm is a progam of short films and at 3:00pm is Mothertongue, Fatherland (2003) a documentary about Amerasians from Vietnam.

National Museum of Women in the Arts

"Women in Cinema: Made in Mexico" focuses on Mexican women directors. On October 11 at 7:00pm is Danzón Maria Novaro, 1991); and on October 18 at 7:00pm is Snakes and Ladders (Bussy Cortés, 1993).

Films on the Hill

"Austrian Exiles" is a multi-venue program celebrating Austrians who came to the US to live and work. As part of this, Films on the Hill shows a series of films by Austrian emigre directors working in Hollywood: Billy Wilder, Erich von Stroheim, Karl Freund, and Edgar G. Ulmer. On October 19 at 7:00pm is Five Graves to Cairo (Billy Wilder, 1943), a WWII espionage film and a two-fer with Austrian Erich von Stroheim as actor. On October 22 at 7:00pm is Merry Go Round (Erich von Stroheim, 1923) a silent film by the legendary extravagant director with piano accompaniment by Ray Brubacher. On October 29 at 7:00pm is a Halloween double feature of The Mummy (Karl Freund, 1932) starring Boris Karloff and the cult film The Black Cat (Edgar G. Ulmer, 1934), the first pairing of Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi.

Washington Jewish Community Center

On October 11 at 7:30pm is Melting Siberia from Israel (Ido Haar, 2004), a video documentary of the director's mother. On October 23 at 1:00pm is a program of two episodes from The Land of the Settlers (2005) with director Chaim Yavin present for discussion following the screening. Chaim Yavin, "the Israeli Walter Cronkite" made excusions into the territories to meet with Jews and Arabs from all parts of the political spectrum. Note that The Land of the Settlers takes place at The Carnegie Institution, 1530 P Street NW, not at the JCC.

Pickford Theater

"Mary Pickford Restored" is a fitting topic for the Mary Pickford Theater. On October 20 at 7:00pm is Hoodlum (Sidney Franklin, 1919); on October 21 at 7:00pm is Coquette (Sam Taylor, 1929) and on October 27 at 7:00pm is Secrets (Frank Borzage, 1933), a Pickford talkie. See above for more Mary Pickford films.

Goethe Institute

Three more episodes of "Metropolis: Eight Film Portraits of Great Cities" are in October with Sao Paulo, A Metropolitan Symphony (Adalberto Kemeny and Rodolfo Rex Lustig, 1929) on October 3 at 6:30pm; Paris 1900 (Nicole Vedres, 1948) on October 17 at 4:30pm and 6:30pm; and Rome: Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945) on October 24 at 6:30pm.

National Geographic Society

The All Roads Film Festival concludes in October with a program of short films by women directors on October 1 at 4:00pm; the DC premiere of The Hunter (Kazakhstan, Serik Aprymov, 2004) at 7:00pm; and the DC premiere of Fifth World (2004) at 9:00pm. On October 2 at 2:00pm is a program of short films from around the world, and at 5:00pm is the DC premiere of The Devil's Miner (Bolivia, 2005) about silver miners in the Bolivian Andes.

The Amnesty International Film Festival begins October 6 at 7:30pm with Darwin's Nightmare (Hubert Sauper, 2004), an award-winning documentary about the introduction of Nile perch into Tanzania's Lake Victoria, followed by a reception and panel discussion. On October 7 at 7:00pm is State of Fear (Pamela Yates, 2005), an award-winning documentary about the Shining Path guerillas, followed by a discussion with the producer and other guests. On October 8 at 1:00pm are West Bank Story (2005) shown with Little Peace of Mine (2004); at 3:00pm is War Games (2005) about an athletic competition in Sudan; at 5:00pm is Mardi Gras: Made in China, a documentary about a bead factory in China; and at 7:00pm is Innocent Voices (Luis Mandoki, 2004), a feature film about a boy caught up in El Salvador's civil war.

On October 15 at 7:00pm is the "Radical Reels Tour 2005," short films about adventure sports--kayaking, snowboarding, biking, etc.

National Archives

"Coming to America" is the theme for October. On October 7 at noon is the 1989 documentary Journey to America (Charles Guggenheim). On October 14 at 7:00pm is The Ballad of Bering Strait (2003), a documentary about Russian teenagers who came to the US to become country music stars. Director Nina Gilden Seavey will introduce her film. On October 21 at 7:00pm is a program about the new PBS documentary series Destination America introduced by producer David Grubin who will present clips and discuss the project. On October 28 at noon is a program of three short documentaries produced by the Office of War Information from the 1940s.

Loews Cineplex "Fan Favorites" Film Series

Horror films and Halloween specials! On October 6 is Interview with the Vampire; on October 13 is Ghostbusters II; on October 20 is Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; and on October 27 is The Exorcist. All begin at 8:00pm.

National Museum of Natural History

On October 1 beginning at 10:00am is the "Fifth South Asian Literary and Theater Arts Festival" including a film at 10:30am Skin Deep (Vishnu Mathur) and 3:00pm In Custody, in tribute to Ismail Merchant. The festival continues October 2 at 2:00pm with Deepa Mehta's film Water, followed by a discussion with the director. Parts 5 and 6 of "Latino Art and Culture" includes the episodes on the Taco Shop Poets of Southern California, history of salsa music and dance in Philadelphia, Mexican American prima ballerina Evelyn Cisneros and more--October 9 at 2:00pm.

The Avalon